Featuring Leah Penniman

Today, 98% of farmland in the entire United States is white-owned. That is the lowest it has been in history. What does this mean for communities of color now? We talk to Leah Penniman of Soul Fire Farm, which heals ancestral wounds and works to end racism and injustice in the food system. Much of the formerly owned Black and brown land was stolen, and is still owned by the descendants of white families. Soul Fire teaches BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) folks how to farm and reconnect with the earth and their ancestors. Leah provides powerful insights on how we can decolonize the land and our minds. From land reparations to acknowledging social disparities to access to culturally appropriate food, she takes us on a journey of healing. Please listen to this critical episode and check out how to get involved. Learn more about their Reparations Map for Black-Indigenous Farmers here. And check out Leah’s book, Farming While Black, a love song for the earth and her peoples.

Colonialism is a term commonly used to describe the dominance of a nation state over a peoples or another country, through the use of social, political, military, and economic force. Colonialism is used to exploit and displace peoples who are Indigenous to a particular place in benefit of imperialists, those whose own interest is the extraction of resources and control of the land through the displacement and extermination of the people who inhabit it.

Call to Action

TRANSCRIPTION

[singing]

Leah Penniman

A couple years into Soul Fire Farm, you know, we’d been running all of these training courses for farmers. Soil health, and cover crops, and you know, pest management. All things you would expect from a farm. And I kept getting these evals back at the end that didn’t talk anything about pH or cation exchange capacity. It was talking about, like, “I’m sober now after many years of drinking,” or, “I left this abusive marriage,” or, you know, “I left a dead-end job and decided to strike out on my own.”

And I was so baffled and a little bit miffed, because I put a lot into my lesson plans, you know? [laughs] And then, and there was this moment when I realized that, oh my goodness, like, sure, we’re teaching this hard skills, quote unquote. But more than that, for many folks, we’re giving them the very first opportunity they’ve had of connecting to the land in a way that is culturally relevant, of their own choosing, sovereign, dignified.

And that’s healing some ancestral wounds. That’s, like, going back generations of healing. And it’s not a lot we have to do. It’s like, make the introduction, let folks touch and interact with the earth. And those tears come, and that laughter comes, and that healing comes. And it has been universal, I am telling you. We’ve had thousands of people come through these programs, and the reflections are like, “Now I understand what freedom is.”

[singing]

Dey Hernández

Hola, and welcome to When We Fight, We Win! I’m Dey Hernández.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

And I’m Greg Jobin-Leeds. Hola, Dey.

Dey Hernández

Hola, Greg. We’re the authors of the book, When We Fight, We Win! In the book, we capture some of the stories, philosophy, tactics, and art of today’s leading social change movements in the United States. Greg and I joined forces to write the book, and now we’re here as co-hosts of When We Fight, We Win!: The Podcast. We hope our show will help you see your role in social movements and learn how to stand up and be fierce, and let the work transform you.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

We’ve been bringing you stories of the people at the heart of the social movements we talk about in the book. They’re radical folks who know that when we stand up to fight, we win. Thank you for joining us for this ride.

Dey Hernández

Today, we’re talking to Leah Penniman. She’s the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm, a Black, Indigenous, and People of Color centered community farm in upstate New York. The farm, it’s committed to ending racism and injustice in the food system and getting more Black farmers on the land.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Soul Fire Farm has three basic projects.

Dey Hernández

One is growing culturally significant African heritage and native crops, using regenerative practices and delivering the food to the door steps of people who need it most.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Two is training and supporting the next generation of Black and Brown farmers.

Dey Hernández

And three is organizing and agitating for systemic change, so that poor and working class farmers of color are no longer oppressed by the corporate, industrial food system. All the work in the farm is done with deep reverence for the land and the wisdom of our ancestors.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

We talked to Leah on June 1st, 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic was raging and exposing deep racial inequities. And right as protests erupted over yet another murder of a Black person at the hands of police.

Protesters

No justice! [crosstalk] No peace! [crosstalk] No justice! No peace! No racism! No justice! [crosstalk] Police! [crosstalk] For the mothers! For the mothers! [crosstalk] No justice, no peace!

Female Protester

My son wasn’t given a chance to live. I have a chance to live, so I will risk whatever it takes to say his name.

Protesters

Marcus Brown.

Female Protester

Say my son’s name!

Protesters

Marcus Brown.

Protesters

Say my son’s name!

Protesters

Marcus Brown

Female Protester

I don’t know all of their names, but what I do tell you is, I stand for all the mothers that, out here who lost their sons to police brutality.

Dey Hernández

Chapter One: The Pain.

Leah Penniman

I think it’s hard to feel like anything is relevant, other than ending the extreme state violence and brutality against Black and Brown bodies. Um, and at the same time, you know, we need to continue to grow food and fight for land sovereignty and all of these long-range things. And so, I do my best to hold a balance of attention, even as my heart is really heavy and devastated by the impact of this violence on our community.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

The idea for Soul Fire Farm started back in 2005, when Leah and her partner Jonah were living with their young children in the south end of Albany, New York, a neighborhood under food apartheid. Food apartheid is one of many ways systemic inequities play out. Some people have access to an abundance of high quality food.

Leah Penniman

And, you know, despite our masters degrees and our high commitment to vegetables, it was almost impossible to get fresh food for our children. There was no supermarket, no farmer’s market, no community garden, no bus transportation to get to the supermarket. And so, the only way we could get vegetables was to pay a fee higher than our rent to join a CSA, which stands for Community Supported Agriculture, and to walk over two miles to go pick up that food and, you know, pile it onto the laps of our children in the stroller and walk back to our apartment, which is completely ridiculous, you know.

So, when our neighbors found out that we knew how to farm, uh, they said, “When are you gonna start the farm for the people?” And Soul Fire Farm was born out of that yearning, uh, just for folks in our neighborhood to get their basic rights of, you know, access to fresh, culturally appropriate food. So we got land in ’06, and you know, the rest is kind of history. We started out with the farm feeding the community, and then layered on all of these additional programs in response to community need and clamor for them.

Dey Hernández

If you’re a white person in the U.S. today, you are four times as likely to have a supermarket in your neighborhood than if you’re Black. And if you’re Black or Indigenous, you’re more likely to have diet-related illnesses like diabetes, heart disease, or kidney failure. It’s, it’s not that entire segments of the population don’t want to eat fresh food. It’s that they don’t have access to it, nor they can afford it.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

And less than 2% of all U.S. farmers are Black, down from a peak of 14% in 1910. Part of that decline was caused by the Ku Klux Klan, who waged a campaign of racial terror and drove Black farmers off their land. Their property was then given to their white neighbors. 20 years ago, the Associated Press conducted a powerful investigation that documented decades upon decades of Black Americans having their land stolen from them through intimidation, violence, and murder. The government was often complicit, approving of the thefts and even participating in them.

Dey Hernández

All of the land that was taken from Black families wound up in white hands. Today, some of the land is still owned by the descendants of the white families who directly stole it. Much of the stolen land has since then traded hands. Some of this land went on to become a country club, oil fields, and a baseball spring training facility.

The Associated Press interviewed more than a thousand people and examined tens of thousands of public records. This research alone uncovered more than 100 land takings, mostly in southern states. Just in these cases, 406 Black land owners lost more than 24,000 acres of farm and timberland. Today, this property is valued in the tens of millions of dollars, and it’s owned by whites or white-owned corporations.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

The full extent of the land theft from Black families is unknown because of a gross gap in public records, often intentional. Here’s an example. On September 10th, 1932, 15 whites set fire to the courthouse in Paulding, Mississippi. This is where property records were held for half of Jasper County, which was then predominantly Black. After the fire, it was suddenly unclear who owned a big piece of the county.

Dey Hernández

When we think about the Great Migration, many of us think about it as six million Black people seeking opportunity in the north. But Leah says it was also a refugee crisis of people escaping terrorism.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

At first, the goal of the farm was to address these issues of racism in the food system and land ownership. Leah was determined to deliver food directly to working class Black and Latinx communities, the people who have the least in Albany.

Dey Hernández

They also set out to train the next generation of Black and Brown farmers in regenerative farming. European colonization devastated the land in many ways, including extractive farming techniques. And Leah started leading workshops that taught regenerative and Afro-Indigenous ancestral-informed techniques that would undo centuries of damage. Techniques that would decolonize the land.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

But that wasn’t enough. While training new farmers, Leah discovered that European colonization left another lasting scar on the relationships that descendants of enslaved Africans have with the land to this day.

Leah Penniman

My friend Chris Bolden Newsome, who’s a Black farmer in Philly, said, uh, “The land was the scene of the crime.” And so, it makes sense that, for people who have experienced, like, slavery and sharecropping and lynching and all of this on the land, that there would be a way that we confuse the oppression that took place on the land with the land herself, right? And name her enemy, name her oppressor. And then flee to those paved streets of Pittsburgh and Boston and Chicago.

But I think that the land was actually not the criminal. The land was probably part of the reason that we were able to sustain ourselves.

Dey Hernández

But there is still powerful intergenerational trauma from slavery, and the land is all tied up in that. Soul Fire Farm set out to heal not only the land itself but Black peoples’ relationship with the land.

[music – “When We Fight, We Win” by Rev. Sekou]

Jorge Díaz

My name is Jorge Díaz, and this is the Word of the Day. The word of the day is colonialism. Colonialism is a term commonly used to describe the dominance of a nation state over a peoples or another country, through the use of social, political, military, and economic force. Colonialism is used to exploit and displace peoples who are Indigenous to a particular place in benefit of imperialists, those whose own interest is the extraction of resources and control of the land through the displacement and extermination of the people who inhabit it.

When we talk about colonialism today, it is important to understand the dimensions of this oppressive system of control and exploitation. First, we need to mention settler colonialism, the replacement of native peoples with a new population to conquer and rule their Indigenous territories and human existence. Also, we need to talk about the colonial rule of non-sovereign territories, the domination of powerful states over the subjugated nations. Thirdly, the phenomenon of neocolonialism, which imposes on so-called developing and underdeveloped sovereign nations economic, political, and military conditions by first-world countries and their efforts to influence and control their geopolitical and social realities. And last but not least, the direct support and promotion of imperialist nations to other states in their colonizing and imperialist efforts of capitalist domination and settler colonialist expansion.

One of the greatest radical organic intellectuals, the psychiatrist, Pan-Africanist, philosopher, and humanist, Marxist from Martinique, Frantz Fanon, states in regard to the greatest colonial power of our times, and I quote: “Two centuries ago, a former European colony decided to catch up with Europe. It succeeded so well, that the United States of America became a monster in which the taints, the sickness, and the inhumanity of Europe have grown to appalling dimensions.” End quote.

The United States is a textbook example of colonialism. Being a settler colonialist state, built on top of the land and blood of native peoples who inhabited what is known as the U.S. mainland. This same nation, which employed chattel slavery of African peoples and after its consolidation embraced imperialist expansion, justified by ideologies of Manifest Destiny and American exceptionalism, entitling itself to invade and appropriate colonies and make them states and unincorporated territories like Hawaii, Guam, Alaska, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico.

The same United States, which uses its imperialist force to implement neocolonialism in nations, specifically those underdeveloped or developing like Honduras, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, and Haiti. Lastly, the United States promotes and supports other settler colonialist and imperialist states like Israel in their efforts to replicate the same genocidal and extractive efforts, which mirror this country’s history. Lately, there are philosophical and practical attempts to address the effects of colonization on a personal and social level, with the concept of decolonization.

Like many efforts co-opted and trivialized by liberals, we must be careful not to fetishize or romanticize the idea of decolonization as a personal, individualistic effort. But rather, engage in collective processes which can move us to address the irreconcilable contradictions of colonialism with a practice that is geared to address the fundamental and systemic problems embodied by the lack of sovereignty and self-determination, which categorizes capitalist, imperialist, patriarchal, white supremacists’ rule.

By addressing these conditions and the system that reproduces them, we can begin to understand that dismantling colonialism is intertwined directly with our struggle for collective liberation. As revolutionary professor and philosopher Angela Davis clearly states in her Expressions of Love and Struggle, and I quote, “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.” End of quote. In essence, decolonization is the ongoing practice of embracing a transformation of reality, which guarantees that when we fight for our own humanity in principle struggle and with revolutionary ethics for our collective liberation, we win.

This has been the Word of the Day.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Chapter Two: The Fight.

Leah Penniman

The journey of healing from trauma as connected to this work. I guess the moment of my awakening around it was a couple of years into Soul Fire Farm, you know, we’d been running all of these training courses for farmers. Soil health and cover crops, and you know, pest management, all things you would expect from a farm and from a science major. And I kept getting these evals back at the end that didn’t talk anything about pH or cation exchange capacity. It was talking about, like, you know, “I’m sober now after many years of drinking,” or “I left this abusive marriage,” or, um, you know, “I left a dead-end job and decided to strike out on my own.”

And I was so baffled and a little bit miffed, ’cause I put a lot into my lesson plans, you know, [laughs] and then, and there was this moment when I realized that, oh my goodness, like, sure, we’re teaching this, these hard skills, but more than that, for many folks, we’re giving them the very first opportunity they’ve had of connecting to the land in a way that is culturally relevant, um, of their own choosing, uh, sovereign, dignified. And that’s healing some ancestral wounds. That’s, like, going back generations of healing.

And it’s not a lot we have to do. It’s like, make the introduction. Let folks touch and interact with the earth, and those tears come and that laughter comes. And that healing comes, and it has been universal, I am telling you. We’ve had thousands of people come through these programs, and the reflections are like, “Now I understand what freedom is. Now I understand who I am. Now I understand that I don’t have to settle for the bullshit,” right?

And that has been probably the most profound aspect of my, my work, now that I get it, right? And, um, something that we articulate now, instead of just having it happen on the side. We articulate that this is a place to come and learn how to farm and also to heal from all that we’re carrying from those generations of land-based oppression.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Leah sees some of the most powerful transformations with the young people who visit the farm. Years ago, one teenager named Kareem didn’t even want to get out of the van when he got there.

Leah Penniman

He was terrified, like a bear would eat him. He was terrified, like something would bite him. And so, the only reason he got out of the van was ’cause we started to take a tour, and he was more terrified of being eaten alone with everyone gone, than he was of being like, eaten in the group. So, so Kareem came with us. And it was, like, super muddy that day. His sneakers were getting messed up, new sneakers.

And so, he decided to take them off and walk barefoot. And nobody listened to anything on the tour. The amount of squealing, you know, with mud between their toes and worms and frogs jumping on their feet, all the things. But we got back to debrief, and Kareem was like, “This is gonna sound weird, Miss Leah, but when my feet touched the earth, you know, a memory of my grandmother came up through my feet, like, into my heart. And she was reminding me about when she was alive. And, um, put, like, bugs in my hand in the garden, and I just suddenly realized, like, I have something to do with this place, and I belong in this place.”

And little tear sheds, you know, and then the other young people are talking about their grandmas and their little tears shed. And, um, so I think even with the young folks who are rightfully skeptical, because they didn’t ask to come out to some farm in the woods, um, there is still that opportunity for meaningful contact with the earth and healing from trauma that comes with it.

Dey Hernández

Unlike Kareem and other skeptical young people who visit the farm, Leah has always found peace in nature. She’s always had a connection to the land.

Leah Penniman

I was one of very few Brown kids in our rural, white elementary school in, uh, central Massachusetts. And to say that kids weren’t nice to us would be an understatement. I mean, my siblings and I were really subjected to a lot of bullying and physical abuse and taunting by teachers and peers. And so, we all found solace in nature.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

When she was old enough to get a job at 16, Leah started working at The Food Project outside of Boston. Each year, they employ more than 100 teenagers from diverse backgrounds, who help build healthy food systems and produce food for city residents, and provide youth leadership opportunities that inspire them to create change in their own communities.

Leah Penniman

And I was totally hooked on farming. You know, there’s something about that elegant simplicity of planting a seed and tending it, and bringing forth the bounty, um, from the earth, that is so undeniably good.

Dey Hernández

But she still learned that the world of farming is dominated by white men. And she began to question her place in it.

Leah Penniman

I started going to all the conferences in the region and reading the books, and very quickly realized that, uh, you know, all of the presenters at these conferences, all the authors of these books on the Chelsea Green table, they were white. And they were mostly men. And I became confused and disillusioned. I wondered if I was, you know, a traitor to my people if my strong back and intelligent mind would be of more service, uh, dedicated to an issue like, uh, you know, housing segregation or, um, improving the public school system in urban areas.

And I had, uh, professors and friends, and I even imagined my deceased grandfather, you know, criticizing my decision, saying, “We didn’t make these sacrifices so that you could go back and stoop on the earth. You know, you have a degree in hard sciences, and you should go and be an engineer or, you know, l-, lead lab research, or work for NASA. And that would be the best use of your intelligence and the best credit to your race, so, why are you trying to farm?”

And I almost left farming. And it took a lot to, to listen to the deeper inner voice that really spoke to the fact that, that this land work is part of my destiny. And fortunately, my mentor and friend, who’s now a board member of Soul Fire Farm, Karen Washington, ran into me at one of these conferences and said, you know, “One day, we will have our own conference. One day, we will have our own book. Just hang in there, because our ancestors are rooting for us, and they have this dream of us being able to return to lands in a dignified, meaningful way. Um, you’re, you’re on the right track.”

And she was absolutely right, you know, fast forward 2010, we have the National Black Farmers Conference and Urban Gardeners Conference. You know, fast forward to 2018, we have Farming While Black, and we truly are part of this beautiful movement of what we’re calling the returning generation of farmers. The folks whose grandparents and great-grandparents fled the red clays of Georgia for a, a quote “better life”, you know? And now are realizing that we left a, a bit of something essential behind. And we’re going back to reclaim it.

The north star of our vision for our movement, um, is that by the next generation, Black farmers will collectively steward a hundred thousand farms on 10 million acres of land in a regenerative manner that provides food and medicine and healing for our communities.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Inequity in the land isn’t just a problem on farmland, of course. The same disparities play out in urban areas. Gentrification and housing displacement in our cities extends to community gardens. Dey has seen this play out in her own community garden in Roxbury, an historically black neighborhood in Boston.

Dey Hernández

I don’t have access to land, but I’m part of a community garden close by. And I constantly see, as gentrification comes more and more in our neighborhoods, um, that the same practices around land and around property and the relationship with land, replicates in those community gardens as well. And, you know, I just have this four-by-six space, and you see how this other things happen in the neighborhood, and how the participation, um. And, and there, and what, what feels to be right for some people and what’s not, and I just, um, I just wanted to hear from you if, if, if you can give that urban perspective in regards to gentrification.

Leah Penniman

I’m so glad you brought that up. Oh my goodness, so glad you brought that up, because we have to remember that urban farming and urban agriculture here on this continent is very much rooted in Black and Brown communities. And so, you look at the work of Hattie Carthan, greening up Bed-Stuy in New York, the work of Demalda Newsome in Tulsa, the work of K. Rashid-Nuri in Atlanta. These are Black and Brown leaders who witnessed the blights, um, that was happening in their community because of redlining, divestments, and then, you know, all of the, uh, mass scale efforts in the 1980’s that put highways, you know, through our communities.

And so, they took these vacant lots, cleaned them up, and built gardens. And these really are our autonomous, sovereign spaces. Um, I spent a lot of time doing urban agriculture, not just in Roxbury and Dorchester with The Food Project but in Worcester, Massachusetts after my baby girl was born. My partner and I were coordinating community gardens and youth programs throughout Worcester. Um, tragically, our daughter had lead poisoning from the gardens, and this was an issue at the time that was not on the radar of the city or any of these organizations. And so, we did massive cleanup with a youth-led cooperative to get the lead out of the soil and make it safe for people.

Um, so, I believe very firmly in the importance of urban agriculture and urban agriculture that’s led by the people most impacted by food apartheid. And I see the same trends that you’re talking about, of gentrification on the macro scale also being manifested on the micro scale, in terms of who is taking control of these community garden plots, how much space they’re taking, the sense of entitlement, the sense of looking down on Afro-Indigenous farming practices as too messy, um, kicking people out of their own gardens, charging high fees for accessing the gardens. And we deal with this in the Capitol District. You know, there’s this one large nonprofit to go unnamed that pretty much controls all the community gardens space, to the point where many Black and Brown folks don’t feel, um, don’t have access.

And so, one of the programs Soul Fire has done, called Soul Fire in the City, is to build gardens in places that are Black and Brown owned or controlled, so people’s homes, churches, schools, instead of these community garden plots. Um, and I know that also in New York City, um, some of the gardens like, uh, the East New York Farms, the Hattie Carthan Garden, they are organizing around this.

I don’t know what the answer is, other than to get the lands into our control. You know, so, one of the things we have been trying to do is start the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust, which is a Black Indigenous led organization that can actually hold land collectively and put easements on it and restrictions on it for certain use. For example, Indigenous Cultural Use or Black Farming Use, so that it’s protected forever and protected from speculation. And that would be a permanent solution to making sure that our farms, gardens, and homes, uh, remain in the control of our community.

In absence of that, you know, I’m terrified of capitalism and its runaway oppression. And, you know, I just think we need to create our land trusts and co-ops and just get the lands in our own hands.

Dey Hernández

Chapter Three: The Win.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

98% of the land you can grow crops on in the entire United States is white owned.

Leah Penniman

98% of the land. Right? And that is a high, all time high, in the history of this country.

Dey Hernández

So, how do we get the land back into our own hands, if it’s not, without a redistribution of wealth and power?

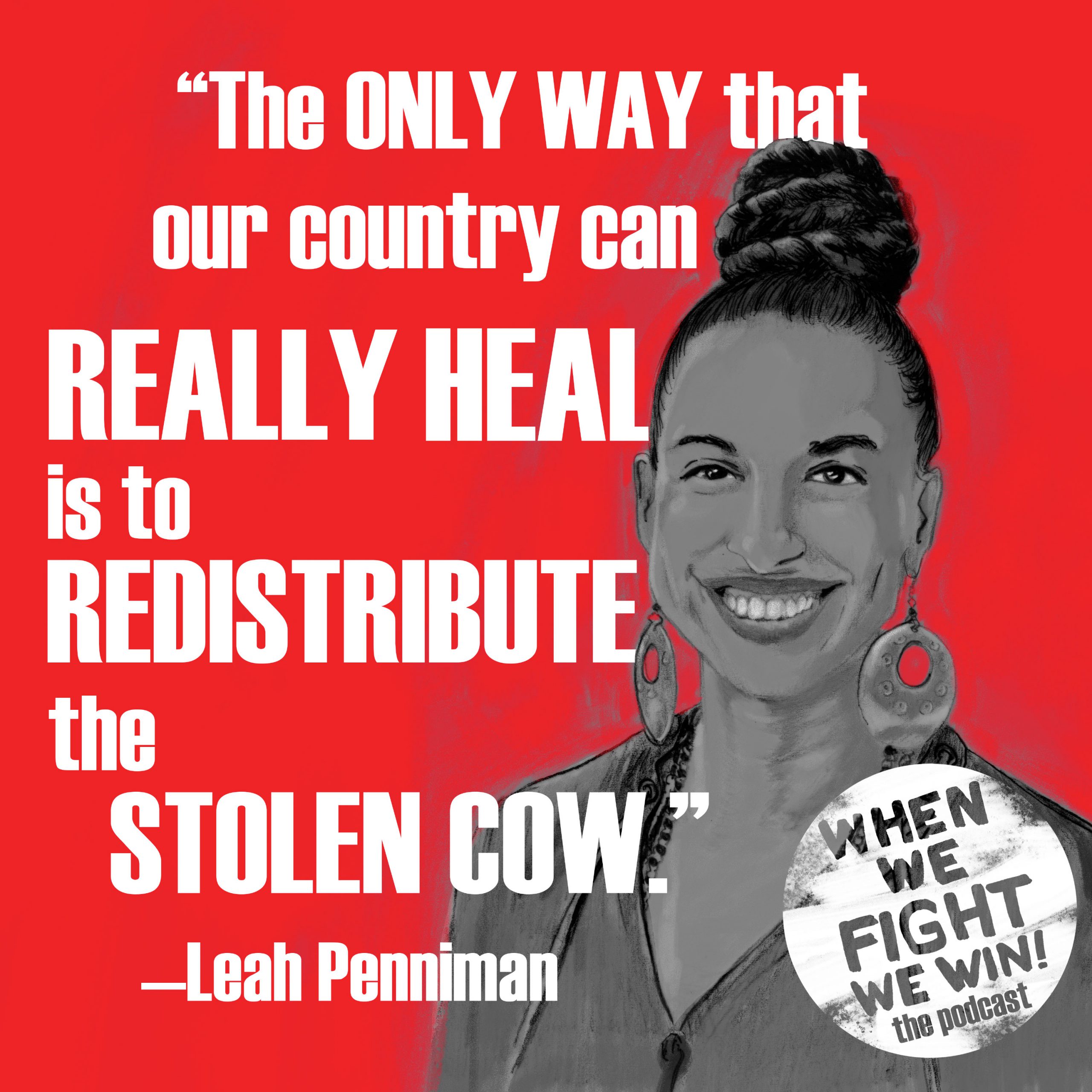

Leah Penniman

I think for many people’s ears, this word reparations sounds really radical and fringe. Um, but my mentor, Baba Ed Whitfield, uh, put it so simply in this one story that I want to share with you. You know, he said, “Imagine that your neighbor stole your cow, and a couple weeks later came over to your house, knocked on your door with remorse in their eyes, you know, apologies on their lips, just being like, ‘I’m so sorry I took your cow. That was really wrong. I know you know I did it. I know I did it. But I’m gonna make it up to you. Right? Every week for the rest of this cow’s life, I’m gonna give you half a pound of butter.’”

I know I would be like, “I would like my cow back, actually.” Right? But unfortunately, the way this country is dealing with a legacy of land thefts, stolen wages, exclusion from governmental, white affirmative action programs and so forth, is to say, “Well, how about we just set up a little scholarship fund over here?” Or, you know, “How about we give out, you know, a couple hundred dollars over here?” And that is the half pound of butter, when really, we’re never goin-, going to address the fundamental gap in wealth, power, and access, until we redistribute land and resources.

And it doesn’t mean everyone gets kicked out of their houses and whatnot, right? You can, for example, put limits on inheritance, so instead of being able to inherit whatever Mommy and Daddy left for you without any limit, there can be a cap on that. And the rest of it goes into a collective fund to be redistributed, right? There could be caps on the amount of land that can be owned. There can be culture respect easements, which is a kind of land sharing, where there’s shared access to land. You know, um, there are a whole bunch of lands that are in legal limbo that could go into trust and on and on. There are many, many technical solutions.

And unfortunately, the political will just isn’t even there. I mean, we haven’t been able to pass HR40, which is just a bill to study reparations and how it might work. Right? But, um, we stand with the Movement for Black lives and their vision for Black lives policy platform. We stand with the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust’s commitment to rematriation and think that the only way that our country can really heal and become truly equitable and live up to its, uh, purported ideals is to redistribute the stolen cow, so to speak.

There is between 4.6 and seven trillion dollars of unpaid wages due to African Americans, and certainly, um, it’s a percentage of white Americans who can trace their lineage back to being, uh, so-called owners of so-called slaves. And then, uh, the rest of white Americans who benefited indirectly from that system, because it did build the wealth of these, this nation. It built the infrastructure of this nation, that in turn led to these profits.

You can, you can go back and think about, you know, the Land Ordinance Act of 1785, or the Homestead Act of 1862. The Alien Land Acts of the, you know, early 1900’s. Uh, air property laws. All of these laws actually result in racial disparities in terms of wealth. You know, take for example, at the end of World War II with the GI Bill. You know, all of these soldiers come home, and the government is giving out 0% interest mortgages. However, in my area alone, of the 67 thousand mortgages that were given out, less than 100 went to a non-white person.

And that is because of redlining. Um, in redline neighborhoods, which are neighborhoods outlined in red as too risky to lend, and at the same time, um, neighborhoods that are specifically designated for Black and Brown folks and ghettoized based on zoning restrictions, um, there aren’t houses that you can buy, because banks have designated them as too risky to lend. You can’t get those mortgages.

And so, a lot of folks, white folks, climbed to the middle class around this time, based on these government handouts. Um, and at the same time, you know, Black and Brown folks were mostly stuck in the same zip codes they were stuck in, working with either predatory lenders or with unscrupulous slumlords. Um, and that is not earned wealth. That is subsidized wealth, you know, supported by the federal government.

And if you were to take away all of these supports, you know, the free land in the West and the low interest loans and, you know, access to free, high quality education and on, and on, and on, um, I think you’d very quickly see that what folks thinks that they have earned is actually based on, uh, the societal disparities that have privileged, uh, white and European people.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Soul Fire Farm has Reparation Demand, an online tool where Black and Brown farmers and land stewards can get direct support for their projects. And so, here’s a place where people with money can chip in, especially those who have benefited from white supremacy.

Leah Penniman

And this might range from, you know, a kind word to a new website, to 40 acres. And people can go on the map and go ahead and donate directly to that farmer, um, to support them. And we’ve had over 30 significant, uh, gifts come through the reparations map, including lands to get folks started. So, that’s really, really exciting.

Um, it’s a stop gap. You know, we really, uh, don’t want to let society off the hook for whole scale reparations, but it’s important to give people the opportunity, uh, to share the wealth that is not really theirs, uh, and do the right thing. Additionally, we got together in 2017, um, in the Northeast, which is the New England states and Upstate New York, about 100 of us Black and Brown farmers, mostly ’cause we were lonely. You know, in, [laughs] in the rural Northeast it’s super white, it’s pretty conservative.

And we were having winter potlucks just to encourage each other. And it only took a few meetings to realize that most of the folks were landless in the group. They were working as farm workers, you know, earning wages or leasing land, oftentimes with insecure tenure. And we started thinking about, how could we collaborate to have more secure land tenure? Not necessarily ownership in the European sense, but a way of guaranteeing that if we invest in soil fertility, that we’re going to get to enjoy the crops, you know, that come a few years later from that.

And it became very important to us as folks who were mostly Black and Latinx, not as many Indigenous folks at the time, to do that in consultation and collaboration with, um, the in-, the original people of the lands that we were occupying, albeit involuntarily for most of us. And I will admit my naivete. I thought this would be an easy collaboration, like, “Oh, yeah, we have a common enemy, white supremacy.” Um, I did not know how deep the divide and conquer strategies of that oppressor have gone over the generations, you know, like seeding mistrust between Black and Indigenous communities and within Indigenous communities.

So, it’s been many years of just relationship building, of, of showing up in solidarity with the Wampanoag land struggles, um, showing up in solidarity as the Nipmuc try to get a historical site back, or as the Mohican fight the E37 pipeline. And you know, building these authentic connections and relationships, and from that being able to draft a protocol of what Indigenous consultation looks like. Um, so that’s still in progress, and lots of bumps in the road as we learn, uh, cross-culturally about how to show up for each other.

But, you know, I have to say that I was really heartened to see a number of Northeast Indigenous individuals and communities make public statements in support of Black lives just this past week, which was not something I saw at the beginning of this collaboration. Um, so I think that we’re building an understanding and building solidarity. And, uh, starting 2021, we will see our first transfers of land. We have folks lined up, committed to give away land, and we almost have our legal structures in place to start to rematriate that land. Um, Indigenous groups get right of first refusal for any land that comes to the trust, um, and if they don’t want or need it in the moment, then it goes to a prioritized list of Black and Brown farmers who are waiting for land. So, we’re super excited, and we hope to change the, the way that, uh, land distribution works in the Northeast.

So, we are looking at this tangible transfer of resources. And in the process of that, um, the healing will come. A lot of the healing from trauma on the land is based on the circumstance that folks find themselves in. You know, to come to a farm that is cooperatively owned, Black and Brown led, that people chose to come to, to learn about the earth on their own terms, you know, to be surrounded by other people who look like them, who have common experiences, to have bare feet on the earth. The earth will do it. I mean, she has been missing our bare feet for generations. She has been crying out in loneliness for us, and so as soon as she has a chance to hug her babies again, her grandbabies again, she does that. And there is a way that that trauma just melts right down into earth. And she composts and gives us back the joy and the hope that we need.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

There’s another important part of healing from intergenerational trauma. Leah describes it as rewriting the narrative.

Leah Penniman

So, when I talk about rewriting our narratives, it really comes from a place of wanting to both acknowledge the truth of all of the wack and oppressive stuff that’s happened to Black and Brown people on land, you know, the bracero and H2A programs, the sharecropping, the convict leasing, the slavery, like, those things are very true. And at the same time, our relationship to land does not need to be defined by those things. It goes back many thousands of years before European contact and colonization and will continue for many thousands of years after. Like, you know, ancestors willing, you know, thousands of years from now, our descendants will look back and be like, “Oh, look at that funny blip on history, where all of that wild stuff happened. Good thing we’re back to ourselves.”

And, and really trying to take that long range is what I mean by, by rewriting our own narratives, and thinking about, “Wow, you know, Cleopatra came up with farming composting, and like, you know, so many of our food preservation methods come out of South Central Africa, and, uh, intercropping and organic agriculture, the CSA, alternative economies, all these things, like, our ancestors were up to these things before slavery and will continue.”

And learning these, these powerful stories of the noble and beautiful contributions of Black, uh, farmers to our understanding of regenerative and sustainable agriculture has been important for me, in terms of reclaiming my belonging, um, in this movement, and ownership over, um, the work to-, towards healing our relationship with the earth.

Dey Hernández

Farm work is hard, and fighting for racial justice is even harder. There may be small wins along the way, but it’s always a fight. When Leah feels like giving up, she remembers how her ancestors, how our ancestors had faith in the future, despite the trauma.

Leah Penniman

So, I think of my ancestral grandmothers, who braided seeds into their hair before being forced onto Trans-Atlantic slave ships, so that I could have seeds, right? And that horror is unimaginable to me, of that moment. And if they didn’t give up on us, right, then who am I to sort of lay down my hoe right now and give up on my descendants? And so, we need to keep on with those strategies, and we need to trust, um, that the force of good, uh, manifest in our actions, is compelling enough that it will eventually transform society for the better.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

And how about the, how about the biggest mistakes that, or most common mistakes that you see folks who want to be in solidarity make?

Leah Penniman

Yeah, I mean, I think one of the challenges is that well meaning, you know, good-hearted, white middle class folks often think and have been trained to think that they know best, and that they should, uh, come into quote “disadvantaged communities” and show them the way. Uh, it has been written about as white man’s burden. [laughs] And I think the challenge with that, you know, and I see this a lot in the food movement, where, you know, the, the benevolent outsider sort of swoops into a kindergarten class of Black children and says, “I know what you need, you know, you all need a kale salad making class after school, and I, Good White Person, will teach that to you. And I will also write a grant to pay myself a salary to teach that to you.”

And meanwhile, you know, the person who’s benefit-, benefiting the most is the kale salad maker with the salary, and these children are not getting a culturally appropriate food. They’re not getting that money that they could certainly use in their families to access the foods they need and so forth. And you know, I, it’s almost so obvious, it’s hard to explain. But, you know, the people who are closest to an issue are the ones who know it best, and I think the job of allies and accomplices is to figure out how to transfer resources to Black and Brown communities, to solve our own problems.

And that’s not as sexy as being on the mic and taking the lead, uh, but to figure out how to get, you know, that 501c3 fiscal sponsorship or that $500,000 or, you know, access to free office space, so that these community groups, uh, front lines community groups, which are often underfunded, um, under-resourced in so many ways, can have what they need to do the work. That’s, that’s it. That’s what allyship is.

[music: “When We Fight, We Win’ by Rev. Sekou]

Dey Hernández

Thank you for listening to this episode of When We Fight, We Win! And this is the final episode of our first season.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

We’re going to take a hiatus to work on season two, so stay tuned for more stories of people at the heart of today’s leading social movements. We’ll miss you.

Dey Hernández

If you’re wondering how you can get involved with Soul Fire Farm’s work, Leah says to visit SoulFireFarm.org and click on Get Involved, and then take action. And check out their Love Notes newsletter to see the farm’s declaration in defense of Black lives and follow their action steps.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

This episode was produced by Mariel Carr and Dey Hernández, and it was mixed by Osvaldo Budet. The Word of the Day segment was produced and hosted by our editor, Jorge Diaz. Yooree Losordo is our managing producer, and Thalia Carroll-Cachimuel is our social media coordinator.

Dey Hernández

Our artwork was created by José Hernández Díaz, and the music was generously shared by Taína Asili and Reverend Sekou.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

We also used music from Blue Dot Sessions. Like what you heard? Please share, subscribe, and rate us. Please follow us on social media, @whenwefightwewin on Facebook and Instagram, @wefightandwin on Twitter. Have something on your mind? Email us at WhenWeFightWeWin.com

[music]