08 Apr Podcast Episode 1: Resist and the Role of Solidarity

Content warning: police brutality, racial slurs, explicit language

In the first episode of our podcast, Greg and Dey talk to musician and activist Rev. Osagyefo Sekou about his upbringing in Arkansas, his passion for music, and the role that we can all play in the movement. Jorge does a deep dive into our Word of the Day, Solidarity.

TRANSCRIPT

Rev. Sekou

My name is Reverend Osagyefo Sekou. I am a blues man, blessed to work in the way that I’ve been able to work, through music. For me what has been interesting is that the music has broken through in ways that my speeches and organizing, I think could not. And so for me, the music seems to be doing something right and all I’m doing is just trying to get back to that little church in Zen, Arkansas. I reached out to the churches of my childhood and I got a band full of church boys so we just churchin right, and we just tryna’ get back home and something about people seeing us get free, that I think makes other people get free.

Dey Hernández

Saludos and welcome to When We Fight, We Win!. My name is Dey Hernández.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

And I’m Greg Jobin-Leeds.

Dey Hernández

We’re the authors of the book When We Fight, We Win!. In the book we capture some of the stories, philosophy, tactics, and art of today’s leading social change movements in the United States.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

During the book tour and since I had the opportunity to learn so much from Dey and our co-author and our editor, Jorge Díaz. Through this podcast, we want to share some of these lessons and if you’re just coming to understand the root causes of today’s growing troubles we hope these stories will flip a switch inside you, our listeners brain.

Dey Hernández

Greg and I joined forces to write the book and now we’re here as co-hosts of When We Fight, We Win! The Podcast. We hope our show will help you see your role in social movements and learn how to stand up and be fierce and let the work transform you. We’re going to bring you stories of our people at the heart of the social movements we talked about in the book. They’re radical folks who know that when we stand up to fight, we win. These podcasts is for everyone who like you, want to listen to the people, activists, artists, and movement organizers that are imagining and building realms of possibility towards liberation across race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and culture.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

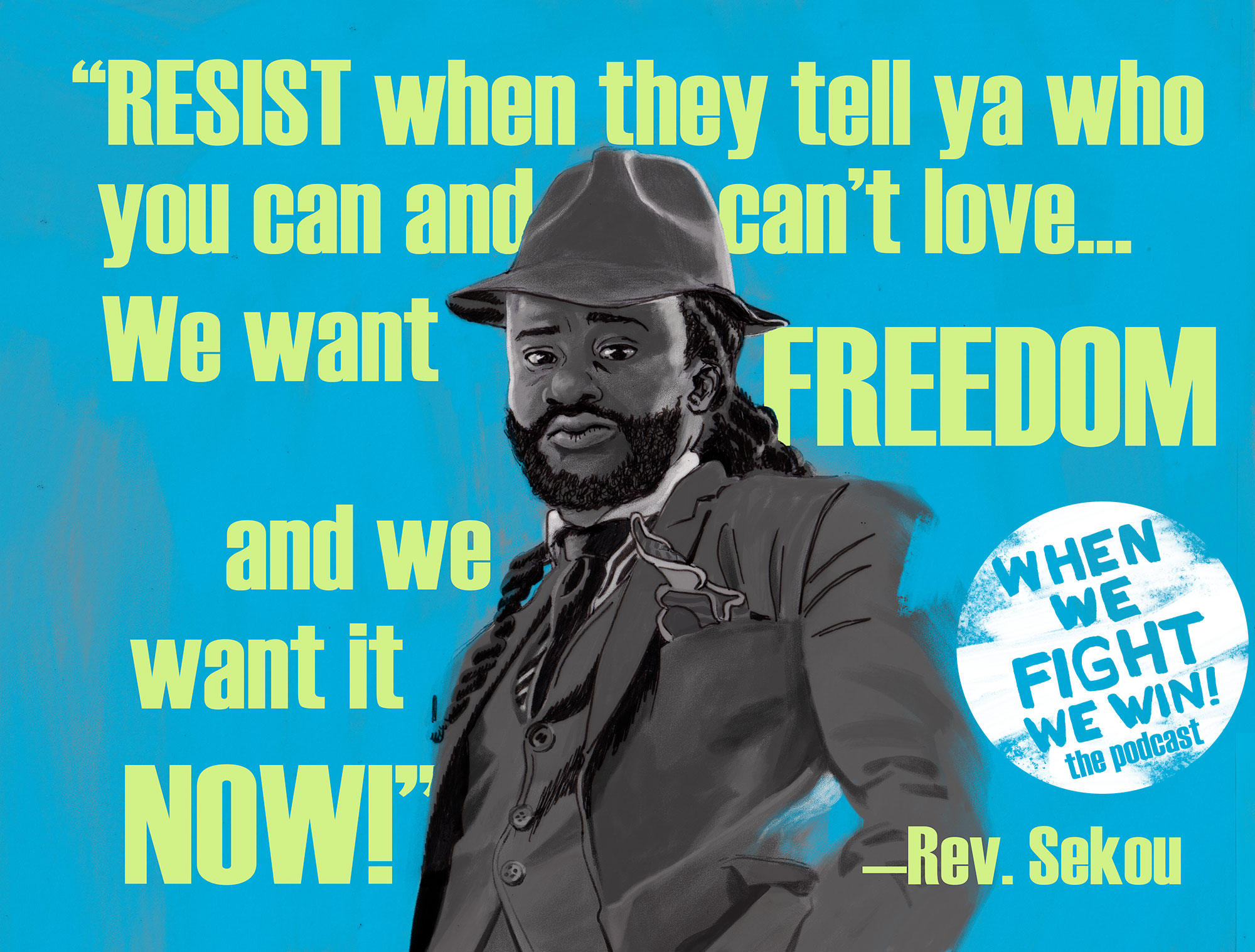

We interviewed Rev. Sekou for our first episode because his music is the backbone of our podcast, but he’s more than just a musician. In fact, Rev. Sekou’s bio is insane, insane in an impressive way.

Dey Hernández

Rev. Sekou is an activist, a theologian, author, documentary filmmaker and musician. His music is a unique combination of Arkansas delta blues, Memphis, soul, 1970’s funk and gospel. His song “We Comin’” was named the new anthem for the Mother and Civil Rights Movements by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His live album “When We Fight We Win” shares the name of our book and now our podcast.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Chapter one, the early pain that grounds Sekou’s work.

Dey Hernández

Rev. Sekou was born in St. Louis and raised in rural Arkansas by his grandparents. He says that this close community made him who he is today.

Rev. Sekou

And so the foundation for me was just that little place that I grew up in Zen, Arkansas with 11 houses and 35 people. It had to do with not only my grandparents, Houston Cannon, and elder James Thomas, but it was Ms. Roberta who couldn’t write her name that taught me to be an intellectual. Or who would say, “come read to me, boy”. Or her, her husband, Mr. Andrew, he said everything twice. He said everything twice. He was my first friend and loved me. He’s probably 60. And I was a little boy, took me to get my first haircut. And so part of this process is that I just grew up in a deep community of deep love and deep care. Now, it’s not to say there wasn’t contradictions and challenges and all of that stuff, but it is to say, that I was deeply loved. And that is what orients me to the world.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

We asked Rev. Sekou how he got involved in movement struggles, and he told us that in some ways it was never a choice.

Rev. Sekou

I mean, at one level, right, to be black in America is to be born into struggle. And the question, at some level, you’re going to always be wrestling with the various ways in which white supremacy and the American empire not only wants to destroy your body, but desires your soul. So that’s the way I was raised, that I knew that the world was a dangerous place. I had to love people, but it could be dangerous to me. And then the question is whether or not you’re going to acknowledge and what role will you play? Are you going to opt in that struggle? Are you gonna attempt to opt out? Are you going to medicate yourself as a way to kind of come to terms with the viciousness and the undignified nature of what the United States can be to black people and oppress people?

Dey Hernández

Rev. Sekou opted in at a very young age after an upsetting and unforgettable experience by the side of his grandmother.

Rev. Sekou

My grandmother, we were at a washing – our temperamental washing machine had gone out, and so we had to go to a, the little laundromat near us, it was near a trailer park. We walked in, there was a little boy. A family that look like me and my grandmother to me at that age, right at four, or five right there was the little boy playing with his cars and a woman, probably mid twenties. So I figured I was gunna play with him, and as soon as we walked in, he was like, “mommy, mommy, look at the niggers. Look at the niggers.” And so I had never heard the word before, but I knew that it was a bad word because the look on my grandmother’s face. So I started crying ‘cause she was angry and she said, “hush up boy, I didn’t run from ‘um when they was lynching us and I’m not gonna start now.” And so the woman was like the 20 something year old woman who I presume was his mother, was like, “you know, I’m so sorry. You know how kids are.” And she was like, “no, I don’t. You taught him that.” And that was the end of the conversation. So me and the boy never played together. We kind of played around each other. And then as we were leaving, the woman was distraught. She was crying. I, and I guess my grandmother discerned as she had run out of money and washing powders. And so my mother, grandmother walked over to her, gave her a roll of quarters and gave her an unopened box of washing powders. And we left. And we got in the car, on the way to the car she says, “boy, you speak truth with grace” and I was like, “yes, ma’am.” And so for me, my radicality begins there.

Dey Hernández

Music has been a big part of Rev. Sekou’s life from a very young age.

Rev. Sekou

By the time I was about six or seven, I sang in five foreign languages. My grandmother got me private vocal lessons, and then I sang in high school. I got a scholarship to a vocal performance scholarship and you know, of course I was in different bands in college. There’s a tragic Afropunk hip-hop fusion band, that I was in called, Africa spell with a K. It was terrible. Oh God I hope none of that ever surfaces. I don’t think we recorded anything, but it was God awful.

Dey Hernández

Tragic Afropunk. I like to hear that.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

By the time he was in college, Sekou was using music to communicate messages of social justice.

Rev. Sekou

I always had a sense of social justice and a sense of what my grandparents taught me. I think I got it earnestly through hip-hop music in the late eighties as Public Enemy, X clan. There was a rise of a certain kind of black consciousness that was advancing through the music that I was listening to.

Dey Hernández

Chapter two: the fight.

Rev. Sekou

In Knoxville, Tennessee. I started at a small, historically black college, Knoxville college. And not too far from there is the Highlander Center, – which has been the center of social movements, particularly in the South. So what a song “We Shall Overcome” was crafted, it’s where King was trained, many of the Snick activists were trying to, where Rosa parks was trained a few months before she sat on the bus. And so I was eventually trained there and mentored there. And so I guess I entered earnestly about 18 or 19 years old.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Rev. Sekou has since helped train thousands of clergy and activists and militant nonviolent civil disobedience throughout the United States. His workshop style trainings have given organizers tools and tactics necessary to support movement leaders who like Rosa Parks, risk arrest.

Dey Hernández

In 2015 Rev. Sekou was a visiting scholar at Stanford University researching Dr. Martin Luther King. Stanford has the largest collection of his writings in the world.

Rev. Sekou

I wanted to write a new book on King and kind of update him and place him in conversation with social movements in the United States, contemporary social movements. You know, the best of what was coming out of feminist and queer theory in, and organizing and young people organizing. But I wound up spending most of my time studying his mistakes. And I just read his mistakes. I look, think through how, how, had he dealt with police brutality. Of course, that brought me to the Watts riots and that kind of thing.

Archived Recording

On August 17th, 1965 six days of rioting in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles came to an end. It started on the night of August 11th when a police officer pulled over a car with two young black men inside. Brothers Marquette and Ronald Frye, a crowd gathered to watch and quickly grew as officers questioned the men, the police presence also grew and the mother arrived on the scene. A struggle ensued. Police beat the brothers. Then they and their mother were arrested. The outraged crowd of onlookers started throwing rocks at police cars. Then at passing cars and buses, the unrest soon erupted into pockets of rioting throughout the 20 block area of Watts. The next day, a community meeting was held urgent calm, but the meeting failed and the outrage and violence intensified. And over the next few days, Watts was turned into an urban combat zone. After six days, the violence ended, but it had taken a heavy toll. 34 people died. More than 1,000 injured, nearly 4,000 arrested and $40 million dollars in damage. Governor Pat Brown convened a commission to identify the root of the riots. Four months, later a report was issued concluding that the riots were caused by a culmination of black residents, longstanding dissatisfaction with high unemployment, poor housing, and inadequate schools. Despite those findings, literal was done in the following decades to address the inequalities. Or to rebuild Watts.

Rev. Sekou

And one of the things that I learned in that study, right, is a timeline, is that when King comes to Watts, the first thing he does is a press conference at the airport.

Archived Recording

Ladies and gentlemen of the press, I have come to Los Angeles at the invitation of a number of concerned individuals and major organizations that have been like myself deeply involved in the struggle for civil rights and human dignity. On the part of people who, for many reasons, feel alienated from their nation, from their families in many instances and from themselves and out of self hatred, self rejection, frustration, seething desperation, the cause of that plight. They unconsciously and consciously turn to these methods. I don’t think that was any individual or group that organized the riot.

Rev. Sekou

So you’ve got to think about 1965. If Dr. King was on TV, people were going to watch right there, not a lot of black people on TV. And so by the time he gets to the community, the community’s pissed at ‘em. Because they feel like, you know he’s going to run the nonviolence thing. You know that he was a little heavy handed and so they were rowdy, they wouldn’t listen to him. And I’m watching a video of it and he’s just really patient. And his staff is like, you need to leave. And he was like, “no at least let me try. Let me try.” So the lesson I kind of took from that was like, you shouldn’t have done no interview before you talk to the community. That would have gone a lot easier for you to go into the community and been like, look, this is the play. Right? I gotta go do this, but I’ll be back. You know what I’m saying? So then when Michael Brown was killed, and I feel like I learned that lesson on a Friday, Mike Brown was killed at Saturday.

Archived Recording

On the streets of Ferguson, MO, outrage and anger. “NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE!” Protestors of different ages and races demanding answers in the shooting death of 18 year old Michael Brown at the hands of a policeman. Investigator said that about noon, Saturday, the officer who hasn’t been identified encountered Brown and another man on the street in an apartment complex. “He’s running this way. He turns his body, towards this way, hands in the air, being compliant. He gets shot in his face and chest and goes down and dies.” Witnesses said Brown’s body lay in the street for hours. The shooting sparked a furious reaction. Police responded in force brandishing assault rifles. Michael Brown graduated from high school earlier this spring and was to begin college next week…

Rev. Sekou

So, I started getting calls from friends, “are you going home?” And I was like, “nah, they not gonna do nothing. Right?” Cause I, I grew up, I went to high school in St. Louis and I was like, “they’re not going to do nothin’. They’ll go home, they’ll go home soon. Right?” So by Monday, journalists started calling journalists that I knew from my time in New York and other activism were like, “are you going home? We’d like to interview you.” And I remembered that mistake that King made. I was like, “nope, not doing no interviews.” And so by Tuesday I was like, I’m going home. So, I didn’t do any interviews for maybe three days, three or four days. I needed to meet people, see who the players were, get permission from the community, if you will, to do interviews. And so I made a decision begrudgingly to go home.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Ferguson would become the largest continuous protest in the history of the United States, longer than the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Rev. Sekou

Basically for 12 months straight there was an action every day in St. Louis. Somewhere in the region someone was protesting, there was, you know, from disrupting theater events, to street shutdowns, to mall, walk marches to people being in front of the police station. The folks just never let up. And that’s in part because there was a thick infrastructure, right? You know, it wasn’t just young people yelling at buildings, right? We bailed out over a thousand people. There was a thick media network and communication strategy. There was a thick network of new organizations ran by young people that was emerging. There was a, you know, it’s like Organization of Black Struggle and Missourians Organizing for Reform. So there was a thick infrastructure in place, you know, included medics, right? As well and live streamers like Bossom, rest his soul, and sister Heather and Short Stacks. Right? There was a whole crew of folks who only did live streaming for us, so there was, because I think it was able to sustain because there was, and then of course MoKaBe’s feeding people for a year for free. The coffee houses, you know, the church Greater St. Mark’s being a place where folks could rest their head and people could come in. So, and then there was an informal network of like community houses that people stayed in. And so throughout that, because of that deep, and thick, infrastructure, the movement was able to be sustained for that long.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

When Rev. Sekou finally spoke publicly. This is what he said:

Rev. Sekou

And though the nation has betrayed them, we will not betray them. Though justice seems far away, may they know that we are close to them and that we are with them and that they might know that they have already won. That they are the inspiration of this nation and we say now to the police, we have already won and you are on the wrong side of history.

Dey Hernández

You know, you were saying that you’re actually not a leader in the movement, but a follower in that movement, that you were taking your orders from 23 year old queer women. What does it mean for you to be a follower?

Rev. Sekou

The, you know, the day of the charismatic black male leader to save us all is over. You know, Martin Luther King ain’t coming back. That’s not a statement of humility on my part. It’s just a different historical moment. No, I worked with a lot of, you know, a lot, a lot of the people who were kind of moving a lot of the street action were young, queer women. And so, you know, they called me up and asked me to train them to do somethin’, I’ll train them. I tell them, I think it was a dumb idea but I’d still train ‘em. And they knew one thing that as a person who had, had the role of kind of articulating the struggle in public space, as one of many spokespeople, and if I could leverage whatever visibility I had before I got there, right in order to serve the struggle, that was my responsibility. And even when I disagreed with them, I would never do it publicly. Now I’d curse them out at my dinner table, of course. But in public, they are our children and so we had to defend them.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Sekou said he still applies everything he learned back at Highlander to his current work, but he’s always adjusting to different situations. What happened in Charlottesville in 2017 forced him to adapt.

Rev. Sekou

So I spent some time in Charlottesville. For six weeks I lived and worked among the people there. And preparation for what was going to be the largest white supremacists March in modern history. And on August 11th we were gathered in a church and we couldn’t leave that church because Nazis were outside with torches. And on August 12th I watched Heather Hyer take her last breath. And so that night we were locked in the church we sang this song, which is become an Anthem for us, it’s called “Bury Me”.

[Music]

Rev. Sekou

I think by the time I got to Charlottesville, which was a different thing because we were dealing with armed non-state actors, right? We knew that the Nazis would be armed and we, so we had to prepare. So in that instance, we called in a woman at the time, Sarah Thompson, at the time was running Christian Peacemakers Teams and so they, you know, they go into arm situations and so we called them in to help train us, ‘cause we were in over our head on it. I’d learned that, you know as an organizer, right? I function two ways. So I was visible in Ferguson because it made sense because I was there but we’ve been in the cities like Charlottesville, it was never made public that I was there. I lived there for six weeks organizing, or when we’ve gone into Charlotte, or when we were in Hartford, CT or Baltimore for a month after Freddie Gray was killed. We fundamentally understood, I learned as an organizer, keeping my head low, giving the people skills that they need and getting out of their way is the most effective so we don’t have to go back to those areas, right. Because they have the skills in that sense. I don’t do Evangelical organizing, meaning this, I am not bringing anything to the people. The people know it. You can walk into any black beauty shop, barber shop, they can fix this country over the course of a haircut and a shade. Right. So I’m not bringing anything to the people. People said, we need to organize single mothers. Have you ever seen the way single mothers organize their resources, take care of each other, lift that, look after each other’s kids? So like when I hear organizers say we need to organize the Black church, I was like, have you ever been to a communion service at a Black Baptist church? It runs with military precision. They already organized. So I’m not bringing anything to the people. The people are in possession of what they need, the issues that can we create this space and equip them with the resources? Right. And, in that and that there is a mutuality in exchange.

Dey Hernández

We asked Rev. Sekou what the word solidarity means to him.

Rev. Sekou

It’s interesting to me, right, so I primarily don’t exist in movement spaces, right? So I’m usually just in a bar or a club or a festival or something like that. Right, so I’m not, I don’t spend most of my time in movement spaces actually, to be honest I find them uninteresting. Right, and so solidarity for me is, so it’s not a political abstraction, but rather it is how, who do we live with? Who do we eat with, right? Right. Who do we break bread with? Whose children do we help bury? Whose hands do we hold when they’re putting their loved ones in the ground? So solidarity means that. That we live, work, and in the suffering and the doings of everyday people than I am all for it. It can’t be reduced to letters of support and holding signs with a variety of political issues from around the world. It’s the question of where do we lay our heads? Who are we in relationship with? How are we struggling with things and what are we struggling against? You know, my thing is until white folks believe that Tamir Rice is their son and that Michael Brown, their son laid in the street for four and a half hours, we don’t win. Until we fundamentally believe, until folks embody that language and believe that their, that their lives are intertwined with other people’s lives. I don’t think we get ahead. I think that for me, that kind of solidarity becomes a real kind of solidarity. You know what King called “beloved community,” and I think it’s just livin’.

Dey Hernández

And that leads us to the segment, the word of the day. With our resident wordsmith and an editor of the book, Jorge Díaz. Jorge is a founding member of AgitArte, an organization of working class artists and cultural organizers that I’m also a part of. We create projects and practices, self cultural solidarity, with grassroots struggles and also lead community based educational and arts program along with projects that agitate in the struggles for liberation.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Everyone on the, When We Fight, We Win! team is connected in one way or the other to AgitArte. I’ve been connected to them for decades.

Jorge Díaz

The word of the day is solidarity. Solidarity is a concept that gets a lot of attention these days, from solidarity economy to solidarity housing it is used in various contexts to signify unity and support. As a political concept it has been juxtaposed against allyship, which is perceived to be less engaged and committed. Regardless of how we decide to define these terms more than a semantics discussion, what we want to focus on are the possibilities and obstacles to a practice of deep solidarity in our work. Even though all efforts to support others can be labeled as acts of solidarity, for many of us organizing in frontline communities, solidarity requires a deeper level of understanding, unity, and action in the struggle for liberation. In our day to day to practice solidarity, we must challenge our levels of comfort and commitment, which unavoidably puts us in a place of having to make sacrifices and decisions for the betterment of the most oppressed and affected by the brutal conditions of the system and society we live in. For situations of uneven power relationships in our lives we must constantly negotiate what solidarity looks like and how in developing the practice, we need to be willing to shift power genuinely through concrete acts, which can strengthen our possibilities for radical transformational change. Shifting power is always tricky and the most affected by power relationships rarely get to decide what those actions are, but it is a critical step. If we are to break down oppressive relationships and systems in organizations, communities, and society as a whole. Solidarity is ultimately about love. Of evolutionary love as Ernesto Che Guevara proposed, one that guides our actions and commitment to end the exploitation of all our peoples and regain our humanity in this world. This has been the word of the day.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Chapter three: the win!

Dey Hernández

For Rev. Sekou music has been a channel of transcending barriers in ways speeches and organizing cannot. His deep rooted faith and belief in the power and beauty of music and art, it’s inseparable from his life’s work and activism.

Rev. Sekou

Well, I think what, at one level, I do think all music is political ‘cause we make conscious choices about what we’re going to sing and what we’re not going to sing. And so that’s one, two, this is three records in “When We Fight, We Win” the live record in Memphis. And so three records in, we’ll see maybe this next studio record might delve more into sentimentality, or questions of heartbreak and romance, which I still think are present, right? So I do, you know, “Loving You Is Killing Me” is a love song about America.

[Music]

Rev. Sekou

I’m really, I’m blessed to work in the way that I’ve been able to work through music, so it just kind of kept going. I kept getting these signs and signals, and for me, what has been interesting is that the music has broken through in ways that my speeches and organizing, I think could not. Charlottesville taught me that we can’t out organize that kind of hate. Right? It was just, you just can’t, there’s no way to out organize it. Right. In terms of, because it’s in the air, it’s, it’s, it’s part of what the cultural studies folks call the Urtext of the United States. It’s, what the French would refer to as the kind of existential ambiance, of the U.S. is one in which you can’t fight through that. And so my experience as a artist has been quite rewarding in the sense of, I’ve seen it affect, so for instance, I’ll tell you this story. We in Waverly, Alabama, we in the bottom of Alabama, we did our show, I got the big band, nine pieces, four thousand drunk white folks, I put my band in Dashikis. We get through with the show, and our CD’s good old boys, staring at me and I’m like, this is going to be a problem, right? And one of them walked out, four of them walk toward me and, and, and one of ‘em walked up to me. He said, “goddammit, I just had a spiritual experience. You son of bitch, you touch my soul.” Now that’s some bitch in the white house, I’ve voted for him, but he got some people not likin’ folks, some of ‘em white and some of ‘em black, and some of them wear Hijab and some of them speak Spanish. What kind of foolishness is there? Fuck him you touch my soul. You son of a bitch and his buddy was like, “you goddamn right.” Or we were in Joplin, Missouri and we go in and do the show and I walk in the green room and the money is in cash, in the green room on the table. So I knew something was up, right. ‘Cause that’s not how it works for artists is like, oh, this is about, there’s a problem if the cash is here already. And he says, the guy who brought us in, he was like, look, we, “I saw three seconds of you. I booked you. I want you to know that my people who come to my shows love music, but most of them are Trump supporters.” I was like, “fine.” And so in that show, I made just one adjustment. I just simply said, “so I don’t care what your politics are, no mother should have to bury her child. On the night that they said that they would not indict Darren Wilson, the murdered of Michael Brown I was standing not too far from his mother and she let a whale out and I just couldn’t shake it. And on the night that we were remembering the killing of Vonderrit Myers who was shot nine times in the back. His mother let a whale out in my chest, and I just couldn’t shake it. Other MUSIC! No, no, no, no, no, no, no. And then when we were preparing the funeral program, Reverend Dr. Johnson, for Antonio Martin, we asked his mother what her son’s favorite color was and she let this whale out and I just couldn’t shake it. So we wrote this song as eulogy for the mothers of the murdered. “Goodbye Baby.”

[Music]

Rev. Sekou

So we do the show, I think we end the show on that. I’m standing outside, people greeting the people as they leave and these good old boys they can’t talk tears rolling down their faces. And, their wives would translate the wiser black guy one of them said, “you touched him” And another wife said, “I think you’ve got to convert tonight.” And so there’s something about what the art does that I couldn’t do as an organizer, as a preacher, you know? So for me, the music seems to be doing something right. And all I’m doing is just trying to get back to that little church in Zen, Arkansas, right? I’m trying to go back to the churches of my childhood of Mount Sinai Missionary Baptist Church and Faith Temple Church of God and Christ. And so I’ll, and I got a band full of church boys, so we just churchin’ right. And we just tryin’ to get back home and something about people seeing us get free, watching other people that I think makes other people get free.

[Music]

Dey Hernández

We asked Rev. Sekou to leave us with a postcard of his vision for a radical imaginary future. And this is what he shared.

Rev. Sekou

Oh, it’s my grandmother’s kitchen table, for everybody is welcome and everybody’s fed. And they’re laughing and joking and their contradictions, and people are mad at each other, but they love each other. Anyway, so for me, it’s my grandmother’s kitchen table. Oh, my grandma’s kids always got some yams on it that we grew. And some greens that we grew in a hog that we slaughtered as a community. You know, it has all the Southern delight on it, some fried chicken and some sweet tea. There’s laughter and we, we prayed before we ate. My Uncle McKinley is there and my Uncle Roy and my Uncle Abrin and my Aunt Barbara, who have all gone home to be with the Lord. My Aunt Gwen who has Alzheimer’s now, who can’t remember me, so she’s at that table and she remembers me. And it’s my cousins and family friends and Miss Roberta, with her snuff bucket sitting next to her. And there’s Mr. Andrew saying everything twice. And it’s just that little ‘ol place that I come from. Right? They weren’t terribly sophisticated people. They didn’t know any of those fancy words that I’ve, I’ve learned at a university or two. They were just good people who loved each other. And they were playing, my Uncle McKinley’s playing, Lou Rawls “Tobacco Road” on the record player because that was his favorite song. So for me that’s what that table looks like, it looks like home.

Dey Hernández

That’s so beautiful. Thank you.

[Music]

Rev. Sekou

Thank you. See ya’ll, it’s been such an honor.

Dey Hernández

Thank you so much for listening to our first episode of “When We Fight, We Win!”.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

We are so happy to be with you.

Dey Hernández

Wondering how you can get involved? Rev. Sekou asks you to check out Memphis For All, which is part of an emergent progressive electorate fighting for democracy, solidarity, and justice inside and outside the ballot box. Check them out, at memphisforall.com. For other ways to join the fight visit whenwefightwewin.com.

Greg Jobin-Leeds

This episode was produced and mixed by Osvaldo Budet and Mariel Carr. Yooree Losordo is our Managing Producer. The word of the day was produced and hosted by our editor, Jorge Díaz, and recorded in San Juan, Puerto Rico by Juan Carlos Dávilla. Parts of Rev. Sekou’s interview was taped in Appleton, Wisconsin by Sean Kennedy. Our artwork was created by José Hernández Díaz and the music was generously shared by Reverend Sekou. We’d like to thank our friends at The New Press, publisher of When We Fight, We Win! It’s available at our website and wherever books are sold.

Dey Hernández

Like what you heard? Please share, subscribe, and follow us on social media. @whenwefightwe win on Facebook and Instagram. @wefightandwin on Twitter. Have something on your mind? Email us at podcast@whenwefightwewin.com.