Season 3, Episode 3, How Do You Shift Your Way Of Giving?

WHEN WE FIGHT, WE WIN!: The Podcast – Season 3, Episode 3 ‘How Do You Shift Your Way Of Giving?’ is out now!

TRANSCRIPTION

Sam: Yeah I inherited $27 million, I think I’ll probably inherit like a hundred million dollars in my life. My grandfather founded a company in the eighties, a tech company that grew and grew and grew. It gave him a chance to accumulate a lot of wealth, um, and give a lot of it back. I decided that I was going to kind of follow in their footsteps, but also put my own, my own spin on it. And so what I’ve been doing since then, since I was 21 or so, is resourcing people’s movements, um, to challenge white supremacy, capitalism, and heteropatriarchy, build a new world.

Greg: The voice you just heard is 28 year old Sam, Jacobs. Sam works in resource development and fundraising at The Right to the City Alliance, which works to stop displacement of low-income people and to protect affordable housing. Sam is a movement donor and focuses his funding on grassroots, social movements.

But some people know of Sam because of his story, which was at the top of a New York Times article entitled “The Rich Kids Who Want to Tear Down Capitalism”.

Dey: Welcome to When We Fight, We Win the podcast. I am Dey Hernandez, your host, joined by my co-host Greg Jobin-Leeds.

Greg: Hola Dey.

Dey: Hola Greg!

Dey: According to the economist Emmanuel Saez, the top 0.1%, one 10th of 1%, of the people in the United States own about the same wealth as the bottom 90% of all Americans combined. And this gap is getting worse. Fast. Our society has become extremely inequitable. In today’s episode, we share the story of Sam Jacobs and his effort to redistribute his wealth to support frontline movements. And while most donors hoard assets and hold onto power, Sam is challenging his family and the donor funder community through his practices.

Greg: What would you do if you inherited $27 million? Today, we get to hear what Sam did and how Sam is challenging, not only himself and his family, but the entire philanthropic field to redistribute their wealth. Through donor networks like Resource Generation, and Solidaire, and through the media, he is encouraging others to follow his good example. That is why he ended up in the New York Times, he wants to change the narrative about money and wealth.

Dey: Occupy Wall Street, Movement for Black Lives, and other movement organizations like The Southern Power Fund and Solidaire have initiated conversations about transforming philanthropy and wealth redistribution. They are beginning to address the power relationships within philanthropy and encouraging a shift to art, real accountability to movements, and to long term unrestricted support from funders to frontline work.

This is critical.

Greg: In season two, we did a two-part episode on philanthropy where we interviewed leaders of the Southern Power Fund and Solidaire. We encourage you to listen to them both. In this episode, we discuss the importance of funders being in solidarity with frontline movements and provide resources and examples on how philanthropic practices can improve.

Dey: The common practice in philanthropy is hoarding assets and holding onto power, and it’s usually led by a small elite of primarily white men. And because money equals power in this capitalist society, many people with money believe that they should be creators of social change. The wealthy benefit from the social capital and political influence they generate through their giving.

The dominant story is that people who make a lot of money work harder and are more competent than those who do not make as much money. And in addition to knowing how to make money, it is assumed that the wealthy must know how to fix society’s problems as well. On top of that, the kids of those same smart people who inherit millions of dollars must be smarter. And so the myth goes on.

But we believe that money’s made by making profits, by making more than needed, a surplus. And that those profits are made off of low wage workers, employees labor, off the backs of service, and immigrant workers. And more often than not, by polluting the planet earth. And of course, by evading and not paying their proper contribution in taxes.

Capitalism is an economic system that feeds up the exploitation of both people and natural resources. It creates vast amounts of poverty, disparities, and climate destruction. In our last episode on philanthropy, actually, Woodard Henderson explains this.

Frontline communities who have been dealing with the consequences of these extractive systems firsthand for years, have the know-how to put a hold on this destruction. The people and systems who are extracting from workers and from our earth are only going to continue reproducing the problems they cause in the first place.

The amount of money that Sam has and will inherit is immense. And Sam is planning to give his wealth away. The idea of giving your money away or redistributing wealth seems outrageous and goes against what is considered common sense in this society.

We need to create a culture where hoarding and having this kind of wealth and money oppose that common sense. Instead, suppose we support each other in creating a collective vision where resources are shared and everyone’s needs are met. In that case, we can potentially live wholeheartedly in relationship with each other and the earth.

Greg: Economic systems are created by humans and their cultures. The type of money that we use is called Fiat money. It’s a currency, not based on a commodity like gold or silver. Our money derives its value solely from the trust people place on it. So our economic system is based on social agreements that are in most of the cases based in ideas and not based on material reality.

If we transform our cultures, we can create new agreements, new economies, and better systems. Imagine, we can create systems that abolish poverty and exploitation. How and what type of new agreement we need to develop is the question we need to ask, and Sam is trying to do this in his own way. His intention is to have new agreements in the service of life, light, companionship, love, healing, and a society that is not divided into economic classes.

Sam: So I grew up in San Diego, in a very beautiful, kind of pristine, seaside town called La Hoya. We took vacations, I was in private school all the way through. And, you know I had every opportunity and my parents were really incredibly sweet about all of this stuff. They said, the reason why we’ve worked so hard, you know, that was always the kind of framing is, we’ve worked so hard to accumulate this wealth is so that you have opportunities to do what you want to do, to be the person you want to be to pursue your dreams. And you know that, was, it was very meaningful, right?

Like I did get to do a lot of very kind of special things and had a pretty carefree, like young adulthood. But there was something that was always hollow to that, which was that, you know, I guess why me? Why, what did I do to deserve that? And what did other people do to deserve not to have those same opportunities? And, and so at a certain point, I got to this place, politically and not because of anything that’s so special about me, but I think because of the things that were going on in the world, which were like the Occupy Movement. People started talking about class and in a way that was really different than I was used to hearing about it.

I was used to talking about wealth with my parents, right? Like that was the only kind of way I really knew how to, engage with it was like we have too much money. We have too much money. We don’t need it. And grandma and grandpa are giving it away and that’s great, but that’s not a full set of solutions to the problems that we’re facing.

But again, it was stuck on this question of like, how much money is there? Who needs it, where is it? And, and when Occupy just kind of burst forward, and I was seeing it on the news I wasn’t anywhere, anywhere close to, you know, Zucati Parker or any of the encampments, even the small one that was in San Diego at the time. It gave me just a new framework to think about, why my kind of sheltered privilege rarefied existence was like so different from almost everyone else, the 99% you know. The more I thought about it, the more I found myself on the side of the 99%. And yet I was kind of stuck in this kind of patriarchal privileged pattern where I was finishing, you know, High School at this tony, very white, private school where I got a great education. I think I learned to think about a lot of these things, but I was surrounded by people who looked almost just like me. And then I was going off to college to study engineering, which was kind of the family trade as it were.

Greg: So then what happens, when do you flip into playing a role in movements, philanthropy, and fundraising?

Sam: At a certain point, I felt like called to action. I grew up in a family that was staunchly Democrats. And so the answer when you have a political feeling or a political, uh, grievance or whatever is, you know, you hit the ballot box or you work within the system.

One of the things that Occupy taught me was, was actually, there’s a whole other way. And that there’s, there is a source of power that comes from people’s movements that kind of refuse to play by the rules that are set out by people more like me or more like my parents or grandparents.

So I was in college and I was starting to read these, you know, like left texts and things that were kind of like blowing my mind. I was learning so much about race, I was learning so much about class, and about history. And I kind of had to seek these things out because I was in engineering school and everyone else there was like beep-boop, working on like computer programming and stuff, not that interested in these questions. So maybe it slowed me down, but I think it kind of slowed me down in a good way because during this time I was starting to think of myself as kind of like a Crusader, and I think a lot of people who, who go through a radicalization process have a, have a phase like this.

And it was a little bit of a heat check I think, of kind of find your place and, and figure that out rather than trying to kind of lead from the front, grab the bull horn, lead the march, that whole thing.

And I think I was like a little intimidated too because I knew what I represented. I would say shit got real when I started inheriting real money from my family. And I have to say a lot of families pass money down in a way that’s really narcissistic and controlling and weird and big props to my family because it wasn’t really that way. It was actually pretty hands-off and no one really like told me what I should or had to do once I inherited that money.

Dey: Many wealthy families, when they pass on money to their heirs, put limits and controls on how the money can be spent and how much of it can be used.

Sam: And so that gave me a lot of space to come up with a lot of cockamamie ideas about, starting to fund left movements and grassroots organizing. That started becoming like a realer and realer possibility. So when I was 20, it was the first time I went to a Resource Generation conference and this conference was called Making Money, Make Change.

Dey: Sam is an active member of Resource Generation. Resource Generation is a membership community of young people from 18 to 35 with wealth and or class privilege committed to the equitable distribution of wealth, land, and power. Sam is also a part of Solidare.

Greg: Sam was already on a path of transformation, but the push he needed to move forward and into action, It came from his cousin who invited him to this conference by Resource Generation.

Sam: It was the first time I went to a Resource Generation conference and this conference was called Making Money, Make Change.

My cousin had invited me, they had been the previous year. They had a really great time. They had learned a ton, they had started to feel like things were clicking into place. And so the whole point of the conference is to turn people like me who were kind of like trench it, like ideological, and kind of annoying, like armchair socialists or whatever into actually useful movement supporters and actors and leaders. And not leaders in the sense, like I was talking about earlier, where it was like, everyone was going to leave this conference and, and take up the podium at, at the next march back when they went home to wherever they lived.

But that the movement takes leadership of all different kinds. And it’s not just the kind of Martin Luther King or Malcolm X type of like charismatic speech, speechifying and your picture on the front of magazines, and your autobiography being, like in libraries for thousands of years to come. We each had a much more actually like bite-sized and realistic role to play.

And for me that was, okay, I have this inheritance, it’s massive, it’s much bigger than I could ever really conceive of using in my life because it’s just more, more money than I need. Why don’t I start there? Why don’t I start by thinking about what I could do with that, and set an example maybe for other people who were in a similar position as me. You know some money that they got handed down by their parents, or, a whole bunch of people I went to college with, ended up working in tech and getting these like kind of wild overpaid jobs. I think the thing that really connected for me, especially in a time, so let’s just, again, set the scene, 2011 Occupy Movement. We’re really like digging in and we’re talking about class, we’re getting serious about, you know, wealth and income inequality. Then in 2014, if my numbers are right, 2014, Mike Brown is murdered in Ferguson and for a white boy like me, that’s like one of the first times I’m really seriously thinking about race and how it affects me and the people who are in my life. And all along the way, the fires in California are getting more and more severe every year. It’s just totally undeniable that like, you know, we have less and less time to address the climate crisis. So like in the middle of all these like interlocking, crises, but also like wake up calls. Look, your wealth and your privilege are only going to keep you so safe from those things.

And in fact, if what you want is safety, you are going to find that if you’re, if you’re feeling safety or if your security comes at the expense of other people, It’s not real. It’s just something you’re, you’re holding onto, out of almost like religious conviction, but actually, we’re all in it. And we’re all vulnerable to these things in different ways, but no one’s really safe from those things.

When I started giving away my inheritance, I was really leaning on this kind of logic that’s like very opposite of what people tell you about wealth, especially like financial advisors or like my parents or whoever, which is that this wealth is something that is supposed to open doors, It’s supposed to make things possible, It’s supposed to open up opportunities. To me, I was starting to realize more and more, that it was actually isolating and it was actually keeping me separate from other people and that giving it away had kind of two happy consequences. Which were that one, people who are doing really amazing, powerful, strategic organizing to counter all of those horrible things that I was talking about earlier, they can actually put food on the table, so that they can keep doing that work. And the second thing is that I would have the opportunity to have deeper, more meaningful, and closer relationships with people because the wealth was actually keeping me isolated.

I think one of the reasons why wealthy people put their kids in private schools and I think one of the reasons why I was in private school was to be around other people who were like me. Because supposedly, that meant that I would be amongst people who would be less likely to want what I had or to be jealous or something of me.

In reality, I think we see how that actually plays out where, these are just like little breeding grounds for the future capitalists of America who then go on and just like steal and exploit other people while patting each other on the back at the golf links. Like that’s not something that I really wanted to stay a part of, I just wasn’t as interested in being around people who came from such similar circumstances as me and, and who just like didn’t have perspective on what, what I was coming to feel was like really important, which was, that everyone has a right to have a dignified, meaningful life and to chase down their dreams like I was told so many times.

Greg: When Sam started to give away a lot of his money, he became more active within Resource Generation. So when The New York Times called to do an article about Resource Generation, he was one of several names that were put forward. Eventually, his story became the first in an article entitled “The Rich Kids Who Want to Tear Down Capitalism”.

We asked Sam what had happened and how he ended up in the story and how his family reacted.

Sam: The New York Times seemed to like rediscover Resource Generation every year or two years or so. And treat us like we’re this bizarre, phenomenon coming out of nowhere and who could, who could possibly believe what these cookie kids are up to. So that’s, that’s kind of the pattern that was playing out like every year for 10 years, is, we would put ourselves out there, some Research Generation members would give them a couple of quotes, and then they would write something that was just so infantilizing and ridiculous, in kind of true New York Times fashion. And what was cool and I guess I got lucky, was that this was really actually the most generous article that they’d ever written about Research Generation. Which hopefully, I mean, the goal of doing all this stuff, is to really try to shift the narrative about, hoarding wealth. And if we, start off in The New York Times with their writers thinking, can you truly believe like these kids are so, stupid or short-sighted or whatever, that they would really give away all this money? Like who do they think they are? To like just enduring this collective trauma of COVID and losing so many people, thanks to all kinds of like endemic issues and American society, in no small part, because certain people had too much and other people lost, you know, 20% of people lost their jobs in the first couple of months of the pandemic. You know The New York Times, maybe is thinking a little differently about wealth redistribution, which is cool.

I agreed to do the interview for the times, it was a little awkward, right, because it was kind of like the heat of the pandemic, things were still really bad in New York. I was working pretty hard at that point. I was doing my fundraising day job, I was working on this other project with my cousin and my sister, to kind of bring some of our friends and peers together who were in kind of a similar class position as us to think about philanthropy, especially during COVID. It felt funny to have this megaphone, to my face, to be able to talk about wealth redistribution and income inequality and that it was going to go in The New York Times. And I guess I felt a little guarded because I’d seen all these pieces that had come out before.

I chatted with the journalist for a while and she was, you know, very interested in kind of some of the sorted details of like, how much money is really coming and, what do your parents think about this and all that stuff. I get that those details are interesting and in fact, I’ve gotten more and more comfortable talking about that stuff. When we don’t talk about wealth, when we don’t talk about numbers, when we don’t talk about this stuff in a concrete way, it really just continues to mystify it.

I told her, I inherited $27 million. I think I’ll probably inherit like a hundred million dollars in my life. I don’t know when it’s going to come. I think that was why I ended up in, at the beginning of the articles, because I kind of did just dive right in and that’s kind of a splashy place to start, I guess. I used some choice terms to describe my family’s wealth. I think I said, you know obscene, I might’ve said like plutocratic. And this interview took place in like June and then the article ended up coming out in November.

Greg: Plutocratic refers to a government that is controlled or ruled by people of wealth.

Sam: And in the time in between June and November, my cousin ran for Congress in San Diego and, and won, became seated as a, as a Congresswoman. And so I think the term plutocratic took on a new meaning that I maybe didn’t fully intend, at the time. But I stand by because my grandparents and their kind of donor class peers really do have the ability to shape the agenda that affects all of us.

That article came out during the week of Thanksgiving and I was spending some time with my siblings and my mom. They maybe just needed a little time to adjust. I think I had chosen strategically, not to mention, that this was coming out because again, like that safety, security thing that I was talking about earlier. It feels really vulnerable to some people to have your wealth broadcast to the world. And you know, it’s true, my brother and sisters didn’t ask me to interview for this article and I didn’t ask them if I, I didn’t ask them for permission either. And so we had a good conversation about who these like taboos about wealth and class, like really serve, and what kind of role they play in keeping, keeping the status quo and keeping wealth redistribution from happening.

Dey: Sam told us that many wealthy families isolate themselves by throwing money at their problems whereas many working-class families rely on mutual aid and solidarity. We asked Sam to reflect on where his sense of safety and security came from.

Sam: I think like a big impulse, among my family and wealthy families in general is, you know, if you have a problem, you just throw money at it. You make it go away, by throwing money at it. And if the problem is, you don’t want to pick up your kids or you can’t pick up your kids from school, you just throw money at it, you hire someone to do that or whatever. And so like the muscle of interdependence gets so weak and it’s something you have to practice like in a society that teaches you that, you have to buy things in order to feel better, in a society that teaches you that, the US is, on top of the world and that, that only happens because we work harder and stronger and better and faster than everyone else. And so anyone who stops to give anyone else a helping hand is, you’re just going to get run over. I think little by little I’m trying to move myself away from, from that. And it can be small things like, my cousin’s basement flooded the other day they absolutely could have called in a team of pros, and gotten that whole thing kind of taken care of. But instead, they turned to us, they made a list of who can we rely on, when the shit hits the fan, they called through that list and I was over there, like in a couple of hours and we started bailing out the basement, you know?

Was it that fun? We made it fun, that’s and that’s part of it too, is like finding community in moments of hardship really makes those things much more palatable. My sister came over too, and she was like, man, if I had to bail out my own basement right now, I would be pissed. But somehow the fact that we’re down here in your place, it makes it so much easier and so much lighter. And so it’s stuff like that, that I almost feel like I’m learning for the first time. You know at 26, that many hands make a lighter load, but not just a lighter load, just like a more fun one and like a more meaningful one as well.

And so, that connects to this feeling that I’ve had, about my wealth for a long time, which is, feeling not totally deserving. Like if I can have this so should everyone. And I try as much as possible to believe that everyone can, obviously I’m down to give up, I don’t know, like Michelin star dinners or whatever the hell, kind of fancy rich people’s stuff I might otherwise be able to do. But that’s not the stuff that’s really important. Like the stuff that’s really important is everyone’s got a place to sleep and food on the table and good school to go to and all that, all that jazz.

The story I shared about my cousin’s basement is very much still all in the family. Being in community with other people without necessarily having to be all up in their space. Those institutions that were part of my life, having teachers who really gave a shit about me, having after-school activities that were really nourishing to my heart and my, my soul, there’s not a scarcity of that, there doesn’t have to be a scarcity of that.

Greg: In the article “Money and the Crisis of Civilization”, Charles Eisenstein echoes what Sam says. He says, and I quote, “If you still have money to invest, invest it in enterprises that explicitly seek to build community, protect nature, and preserve the cultural commonwealth. Expect a zero or negative financial return on your investment. That is a good sign that you’re not intentionally converting even more of the world to money. Whether or not you have money to invest, you can also reclaim what was sold away by taking steps out of the money economy. Anything you learn to do for yourself or for other people without paying for it, Any utilization of recycled or discarded materials, anything you make instead of buy, give, instead of sell. Any new skill or new song or new art you teach yourself or another, will reduce the dominion of money and grow a gift economy to sustain us through the coming transition”.

Dey: In the article “Philanthropy’s a Scam” author Julieta Caldas says that philanthropy uses the term giving, but it is euphemistic. Giving, stresses the generosity of donors. Caldas states, and I quote “When it comes to the objectives of the giving, many state that it is not only a social obligation, but potentially healthy for business. Hence, why profits never really suffer, even when the billionaires give away large portions of their shares. That given, therefore, has the explicit dual aim of maximizing social benefit and return on investment”.

Greg: So often we see donor and funder relationships, foundation, and NGO relationships, rooted in this false expectation that because we give, we deserve something in return. Many foundations and wealthy donors expect a return from their donations. It’s a part of the plutocracy that Sam talks about, the wealthy, controlling donations and government, the wealthy end up controlling the private and the public sectors. But our grassroots organizations don’t owe anything in return, what they deserve is proper funding.

As The Southern Power Fund refers to it, we need to move from philanthropic grant making to movement redistribution. We need to move from grant seekers being asked to justify why they need a grant, to shared accountability that goes both ways. We need to move from rapid response grant making, to grassroots groups intervening before crises happen, intervening during and intervening after crises. And move from the grassroots groups, making requests or asks of donors to inclusive invitations.

This Southern Power Fund model moves us away from the donors having all the power. We can uplift this and support movement redistribution in the philanthropy sector and beyond.

Now, back to Sam who talked about some of the obstacles that were placed in front of him, preventing him from moving more towards a gift economy.

Sam: It’s almost like learning a whole other language, you know? Because I learned pretty early on that if I was going to be really loud and proud and honest about what I was trying to do with my wealth, there were going to be many people who were paid to stop me. And whether they were stopping me on purpose or whether they were stopping me just by not kind of showing me the way, I did ultimately kind of have to figure some stuff out for myself. And so, I think a good example of this is, my family, my grandparents do a lot of giving they’re very philanthropic, but they don’t have a family foundation. There wasn’t really a place necessarily for me to gain just familiarity with how philanthropy works. They set up these funds for me and for all of my siblings and cousins to like, I guess, experiment to, to just try giving money away and see what happens, but without much in the way of like training or guidance. Which again, I think is cool because, in a lot of cases, people do this shit just to control other people, especially their families, which is totally upsetting, but, yeah, this was really freeform.

Dey: We asked Sam how he calculated how much money he could give.

Sam: I guess my, my engineering degree came in handy a little bit here because, you know, I, I think organizing and giving and all that stuff is like, you’re in a box, you have these constraints and you have to kind of do the best you can in that situation. And so I started learning about like, okay, I have these trust funds, I hear all these things about how when you have a trust fund, that means you have lawyers. That means there are all these different kinds of people who are paid to, paid to make your wealth grow. And I was trying to do the opposite. I went to a lawyer’s office and I think I asked them questions that were different from the questions that a lot of other people ask them, which is okay, so, given these terms, given the way the trustis set up, that means that I can, or can’t take all of this money out and, give it to other people or whatever.

And in most cases, the answer was, no, you can’t do that at all, like why would you even think that. It’s obviously not set up to do that, It’s set up just for my personal benefit. And so I started learning the rules a little bit and like reading these like long legal documents that buried somewhere inside, you know, 40 or 50 pages of legal ease, I finally found Sam has the right to request a 5% distribution every year. The interest and the dividends from this fund will pay into Sam’s revocable trust. And it was total word salad, I didn’t know what any of this stuff meant at the time and so I had to learn some of that stuff.

But it was so interesting to see just how made up it all really was. I had this image in my head, my trust fund was something that was like behind a lock and key, or in a vault somewhere, in a dungeon guarded by a dragon or something like this. And in fact, it’s just money in a bank account. The thing that makes it tough to break that down is not because there are any like, yeah, it’s not like I have to pick a lock or it’s not like I have to fight, go on some medieval quest, it’s that there’s tens and hundreds of people whose jobs it is to uphold these rules that in most cases like my parents decided and they decided kind of without asking me.

And so like basically what I’ve been doing is kind of threading this needle. Seeing kind of how much I can get away with before someone decides, all right, Sam his whole, like socialist charade is, is cute and all, but it’s gone on long enough, so let’s, let’s shut him down. And, and so just staying slightly on the right side of that kind of line has been the move.

So when I started, when I was 21, I asked for a small piece, you know, like I asked for, God, I don’t remember the numbers, but maybe like, can I have like $150,000 to give away? And that’s where I started. And so I started talking to people who would come and fundraise me and ask me for money. And so I would try to learn a little bit here and there about, okay, what is this, what is this whole grassroots organizing thing? How does it work? Like what does it mean?

And, next year I asked for more, maybe double that. And then the next year I asked for double that again and I kept going up and up and up. And so, last year, I gave about three, about $3 million away. And I, again, kind of had to bump into some of these like rules and regulations. Because what I had really wanted was to kind of come up to this level, which in a normal year, would mean that actually I was starting to spend the amount of wealth that I had down and down and down, and it would get smaller and smaller and smaller until I’m a normal person. And so what I realized is I finally made it up, I was like working towards this, I was, giving away $3 million is not to play the world’s tiniest violin or anything, but it actually takes, it takes a good amount of work. It takes like relationships, it takes organization. It takes a little bit of a strategy, a little bit of thinking, and a fair amount of time.

So it was something I was doing kind of on top of my day job. And, there, there are plenty of like foundations with five, ten staff that do that amount of grant making. And so I was like very excited. I was like, all right, I’ve got these organizations that I really like love, that I think are doing really powerful work. I’ve been funding them for a long time and I want to keep funding them for a long time. And then I like ran up against this wall and I found out that I was only like guaranteed to be able to do that because there was a special kind of, clause in the trust that said that when I was 25, which I was last year, I could take out like 25% of the amount in this trust. And so that was like where I drew most of the funds to do this giving. And so it was going to last me through this year, but then I had to, I had to go back and ask for more and basically, it was kind of up to my uncle, whether he decided to say yes or not.

Dey: Sam went on to further explain his role with other people of wealth.

Sam: I think part of my job, part of the, the burden I have to carry or whatever is, is doing that, that sort of translation work. Because if my goal is to bring more people and open up more resources for people’s movements, then I, I’ve got to be a hype man. I’m not going to lie, I think doing that translation is important. I try to approach fundraising and resource mobilization as an organizer, I’ll sit down with someone I’ll, but I try not to talk as much, I try to actually do more listening and I try to hear like, oh, that’s interesting that you said that you think that the public education system is really racist. Like, what, what makes you say that? Or what makes you think that? And then I know I have a kind of in there. Like sure, they may not be interested in totally like transforming our economy and society, but, yeah, okay, you think that you think the public education system is racist? Let’s, let’s go there. Let’s talk about how that figures with wealth, let’s talk about our experiences being outside of that system and looking in, or, what are some of the things that you were taught about, who, who is deserving of a good education and all of, stuff like that.

I did have to learn that arguing and organizing are not the same thing. As much as I would’ve liked to believe that they were because, because actually I can, I can win an argument pretty well, but that doesn’t actually necessarily mean that someone’s gonna join the movement. And, and in fact, it’s less likely on the other side of it that they will.

There’s, there’s a version of my story, makes me look like a martyr or something that makes me look like someone who’s making a sacrifice. And I, I am certainly not a martyr. I work pretty hard, I take this shit seriously because it matters, but I’m, I am not struggling over here.

Thinking about like The New York Times article, for example, it’s, to a New York Times reader, to your average, you know, 50 something white-collar worker from, Suburbia or wherever. My story is, is probably more interesting to that person than say the work that I, he thought that I was doing, like then the powerful, powerful organizing that y’all are doing, or, it’s, maybe my story is more interesting than like The Movement for Black Lives story to, to that person.

And so, there’s, there’s this element of, of trying to be strategic about whose story we tell when and where. Because if me telling my story, sure, maybe like the first couple of times I did it, especially in the, the paper of record, I felt a little uncomfortable. I felt like a little exposed or something, but, if me telling my story in the times means someone who’s like me is going to read it and it’s going to, it’s going to open their mind a little bit about their position in the world, and what they, they can do, whether they have wealth or whether they know people with wealth. That’s a small, It’s like a small victory.

Dey: And this leads us to the word of the day with Jorge Diaz.

Jorge: The word of the day is philanthropy. Philanthropy is the transfer of resources from wealthy individuals, usually through organizations called foundations to social movements and organizations. These organizations are typically classified in the United States as nonprofits. Exempting them from taxes and exposing them to government regulation and control.

Philanthropy as we see it today began in the early 19 hundreds when wealthy elites like John D Rockefeller, who got their millions through capitalist exploitation, created foundations as a way to filter the money towards charitable causes of their choice, but mainly to shield their wealth from taxation. Today, foundations are only required to donate 5% of their total assets annually. Which means that currently, foundations are hoarding over $1 trillion in assets. This centralizes money in the hands of the privileged few, instead of spreading it to the working class people who generated it. Historically, philanthropy has weakened or deradicalized social movements. Wealthy funders have often focused on individuals suffering from the effects of capitalism and white supremacy, rather than the oppressive system itself; it has also served to distract from more radical wealth redistribution efforts and to replace the state by providing privatized services, which were once public. This corporatization of philanthropy and its political implications is outlined and detailed in the critical book, “The Revolution Will Not be Funded” written by various authors and compiled by Incite, women of color against violence. Wealth exists because of the exploitation of the working class, and can be traced back to the enslavement of Africans, the genocide of Native peoples, and the exploitation of the labor of workers, specifically immigrants. There are many groups working to shift philanthropy from its white resource hoarding origins, to a more diverse, expansive and accessible form of wealth redistribution. To be part of that movement, funders can stop requiring excessive grant applications and reports, and donate generously to grassroots organizations. Particularly, funding their organizational capacity building and long-term projects.

There are many incredible organizers and groups doing the hard under ground work that is sustaining community and building new futures today. If wealthy people are interested in the real change that comes from shifting power, they can give their money directly to these efforts while spending down their wealth without requiring numerous hoops to jump through or strings attached.

As Highlander center’s co-director Ash-Lee Woodward Henderson states, “Fund us, Like you want us to win”. This has been the word of the day.

Dey: Now back to Sam.

Sam: What is, what is philanthropy for it? Is it, is it really about generosity? Is it really about giving of oneself? One’s time, one’s resources. If it were, I think we would see over the last 40 years as philanthropy has really kind of evolved into its current form, we would’ve probably made some pretty serious headway on these incredibly massive issues that we’re, we’re facing.

And interestingly, those things have all gotten much, much worse, you know? And, and, it’s just true on a quality of life level. And so, you have to ask the question like this myth of generosity, what’s that about, and who does it serve? And this is straight up the middle left critique of, of philanthropy, but it’s not, it’s not really about, you know, it’s not really about solidarity. It’s not really about, like evening the playing field, it’s about really, it’s like a, it’s like a reputation laundromat. Where someone like Bill Gates, who was like incredibly unpopular in the nineties and who was seen as like the scourge of the business world, because he was such a ruthless monopolist comes out on the other side, looking all squeaky clean, like he is going to save us from climate change.

Like it’s magic, it’s like magic. And, and, and so the question then has to be, okay, what are the kind of like self-reinforcing practices of philanthropy that are just leaving all of these horrible systems in place? And in fact, allowing them to get worse while more and more money is moved than ever before?

This whole generosity thing is funny because I think I get more free stuff as a rich person than anyone else that I know. Like, for whatever reason, that’s who gets gifts. When I go with my dad on a business trip or whatever, to spend some time with him, I’m always just shocked at like the amount of stuff that rich people give other rich people for free and rich people are, are just the most generous with, with other rich people.

And if you look at the way that philanthropy works, how much money is actually moving, out of the billions and billions that are given every year, how much of that money is going to organizations that are led by working class people, that are people of color led, that are actually striving to change the fundamental way that our economy and our society are set up?

It’s really very little, it’s like just vanishingly small, it’s mostly like these bizarre, vanity projects, like, you know, building a new wing of the ballet center that’s got the Koch brothers’ name blazing on the side. And so, which is no shade against ballet, but, I think, I think we’ve got, we’ve got bigger concerns.

And so yeah, the question is like, can we use philanthropy as a tool to undercut the very system that created philanthropy in the first place? Philanthropy is really just an outgrowth of the fact that people don’t have what they need in this like most, just like the wealthiest, like most quote on quote advanced society that has ever existed on the face of the earth.

The fact that people don’t have what they need should be just like a moral failure. And instead, it’s an opportunity for rich people to justify their own existence by saying, well, without us, you wouldn’t have that library downtown. Without us, you wouldn’t have the nice museum to go to or, or whatever. And, even a lot of these things are like out of reach for, for most people who are literally working to create the wealth that then these philanthropists so generously give back.

Greg: Sam, is there another way for philanthropy to move forward?

Sam: You know if you strip away all the bullshit from philanthropy, you have something that’s, that’s really profoundly human at its core right? Which is that people actually do tend to take care of each other, you know, people actually do have an impulse to look after each other and not just fuck each other over.

Philanthropy takes that idea and turns it into its worst, most capitalistic like vulture format. But I think it’s, I have to believe that that’s a core part of, of being human.

When I, yeah, when I think about a utopian future, a classless society, one where like we all have our basic needs met. I think a lot of the stuff we do is going to be philanthropic in some way, in terms of you get a bunch of people together and people decide for themselves like, you know, through community self-determination how they want to spend the resources that they share.

And now, that’s not where we are, in fact we’re nowhere fucking near that. And so I think where your question is getting at too is like, can we build a bridge from here to there or like a tunnel or like can we fly a plane, a carbon neutral jetliner to get there, you know? I think there’s like a lot of kind of inroads, which is maybe daunting, but also exciting because like, I don’t know, like I was saying earlier, you carve out your bite size part of it, and that’s the thing you work on and you organize your pals and, and your other people to work on the other stuff. And people have been working on this for a really long time, which is good.

Philanthropy is in, maybe it’s not a full-blown crisis, but it’s definitely having, maybe it’s like some adolescent identity crisis kind of stuff. Where like philanthropy is looking at itself in the mirror and it’s not the cute kid that it used to think it was, it’s getting some acne, its voice is sounding a little weird. It doesn’t totally recognize itself anymore. And the world is changing around it too, you know? And so philanthropy is seeing itself and some of it’s, some of it’s ugly, stuff that it has tried to hide for a long time. And like what an opportunity for us to push and push and push to not let things like racial equity, and disability justice and actual democratic decision-making become just like buzzwords that philanthropy picks up and uses when it’s convenient, but then drops the second that it gets hard because that shit is really hard, fundamentally, and going to your cousin’s place to bail water out of their flooded basement, it’s, it’s hard and meaningful. It’s both in fact, like the easy stuff never really is.

And so, I tend to think of philanthropy as, the dust that blows off the stacks and stacks of money that people have been hoarding, over the pandemic. And since the movements that I’ve been lucky to be a part of, that y’all have been leading, are not asking for the dust that blows off anymore. We actually want, we want the whole thing. And, just to get kind of really nitty gritty about it, there’s this rule about foundations, they only have to spend out 5% of the amount of money that they have in the bank. And so, 5% of say the Ford foundation’s budget, not budget, the endowment is going out the door. Well, about 20% of that is going to like water the plants in their very beautiful atrium in their New York headquarters. And then, but what does that mean? It means 95% of that money is just it’s not just sitting there, it’s actually going and making all the problems worse that all these people over here working on. So if you think of it like a seesaw or whatever, it’s like you got 5% on this side trying to alleviate these problems and you have the whole rest of the 95% just tilting the balance, in the opposite direction, making it worse and worse and worse.

And what if we could change that balance, right? We can, it’s just a rule in the tax code. So, imagine if we could take that 5% and we could crank it up. And we can crank it up even more. We could get it to 10%. We could get it to 15 or 20.

And you’ll have people who will say, oh, but what will we do? These foundations, they won’t be able to exist in perpetuity. And we will say, excellent. We will say that is such good news because no one actually asked them to exist in perpetuity, right? We’re dreaming about a world in which we, we don’t need to have a Ford foundation anymore. And so that’s the vision, right? The vision is the abolition of philanthropy. We are going to find other ways of sharing and giving amongst ourselves and each other without needing a nonprofit board or, these fancy degrees or whatever, that make the Ford foundation what it is, because I think it’s part of what we do. It’s part of who we are, just like baked in.

Greg: Abolition of philanthropy? Yes. Who are the wealthy to be the ones to control the giving. It is anti-democratic. If we want to create a new society, we need to normalize things that are not normal. We need create a new economic system and a society where it is natural, where it’s normal to share your resources and to share wealth between all human beings.

We need to normalize the gift economy. We need an economy that cares for the planet and all of its beings. We need to abolish the extract of economy. Abolished debt. We need the abolition of hoarding, exploitation and poverty.

Dey: When We Fight, We Win the podcast is a project of Agitarte Media. This episode was written and produced by Thalia Caroll-Cachimuel, Greg Jobin-Leeds, and Osvaldo Budet. The word of the day is written by Meesha squazinbarner and Jorge Diaz.

Thalia Caroll-Cachimuel is our Communications Manager. Our theme song is by the one and only Reverend Sekou. Please check out his music available across all streaming platforms.

Visit our website agitarte.org to support and donate to a project. You can also visit our store for swag and to buy gifts. We have posters, downloadable resources, stickers, and dope T-shirts with powerful messaging. Hit us up on social media or via email to let us know what you think. Or to keep up with our podcast, please follow us on social media: Twitter is @wefightandwin, Instagram and Facebook are @whenwefightwewin. You can also visit us at whenwefightwewin.com where we have plenty of resources for organizers, activists, and donors.

Greg: For more information on Solidaire, please visit their website at solidairenetwork.org. And to learn more about Resource Generation, visit them at resourcegeneration.org.

You can find links to the Southern Power Fund at Resource Generation or at our website: whenwefightwewin.com.

Dey: We will publish a new episode every two weeks on Mondays, our podcast is available across all streaming platforms. All of our episodes are on Agitarte Media Production. Thank you for joining us. I am Dey Hernandez.

Greg: And I’m Greg Jobin-Leeds. Thank you so much for being with us today.

The word of the day is philanthropy. Philanthropy is the transfer of resources from wealthy individuals, usually through organizations called foundations to social movements and organizations. These organizations are typically classified in the United States as non-profits exempting them from taxes and exposing them to government regulation and control.

Call to Action

Monday, April 4, 2022

Greg Jobin-Leeds

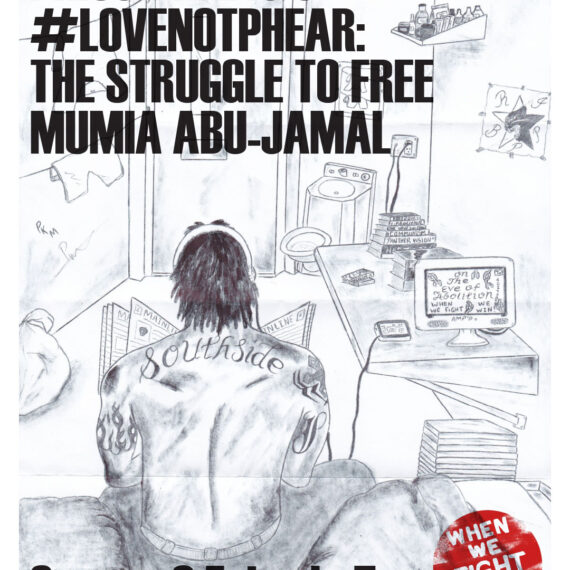

–Covering Up The Mold at WHV featuring Krystal Clark –Overcrowded at Women’s Huron featuring Quiana Lovett –Prison & Slavery featuring Kevin Rashid Johnson -See Kevin Rashid Johnson’s Artwork on Prison…

Monday, April 4, 2022

Greg Jobin-Leeds

-Engage with Prison Radio’s content and campaigns on their website, by subscribing to their email updates, and following them on social media @prisonradio. You can In the summer of 2021, AgitArte began corresponding…

Thursday, March 24, 2022

Greg Jobin-Leeds

Engage with Prison Radio’s content and campaigns on their website, by subscribing to their email updates, and following them on social media @prisonradio. You can also listen to correspondents of Prison Radio on their website…